A Six-year Analysis of Sex Traffickers of Minors:

Exploring Characteristics and Sex Trafficking Patterns

Arizona State University Office of Sex Trafficking Intervention Research

Dr. Dominique Roe-Sepowitz, Cmdr. James Gallagher, Kimberly Hogan, Tiana Ward,

Nicole Denecour, Kristen Bracy

ASU STIR research students and staff provided research assistance: Lisa Leary, Rachel Frenzel, Jiwon Byun, Karen Catano, Savannah Lane, Caitlin Haden, Chae Chavez, Tevor Lazar, Ryan Norton, Kate McGlynn-Moore

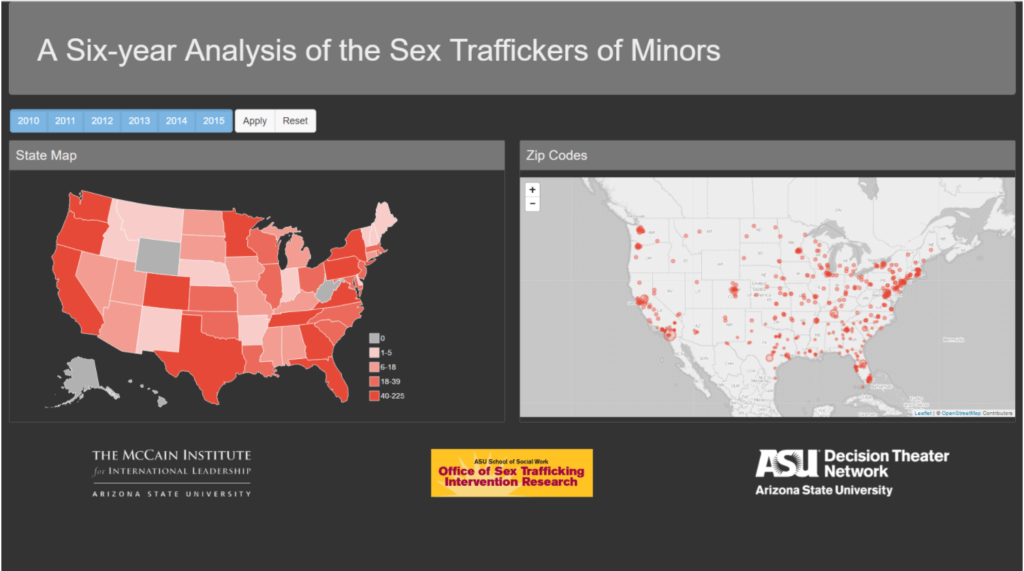

View all data in this report through this innovative interactive web tool.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introduction

Sex trafficking is a pervasive national problem in the United States. Media reports indicate that sex trafficking occurs in both rural and urban areas with victims who are children and adults, of any gender, race, and sexual orientation. Sex trafficking, defined by the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2000, is the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, obtaining, patronizing, or soliciting of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act. For persons over the age of 18, the TVPA (2000) requires the demonstration that force, fraud, or coercion was used by the sex trafficker(s) to be considered a sex trafficking victim. Persons under the age of 18 (minors) are not required to demonstrate force, fraud, or coercion related to the commercial sex act to be considered a victim of sex trafficking.

Due to the covert nature of sex trafficking activities, creating reliable statistics on prevalence, frequency, geography, and particulars of sex trafficking have been difficult to develop (Clawson, Layne, & Small, 2006). Over the past decade, the Federal Bureau of Investigations has reported that they have assisted in the arrest of more than 2,000 human traffickers of both sex and labor trafficking (Human Trafficking/Involuntary Servitude, 2016) but sex trafficker-focused research primarily has relied on small convenience samples with limited ability to compare across time. This study uses a systematic search method to determine the incidence of arrests for sex trafficking of a minor in the United States from 2010 to 2015.

Research and Methods

This report uses data collected through a structured online search that produced a six-year picture of the arrests in the United States of the specific charge of sex traffickers of minors from 2010 to 2015. The findings from this report include individual and case details including characteristics of the sex traffickers (age, gender, race, professions, and gang involvement), details about how they recruited and victimized their minor victims, and information about their case resolution. A web-based information dashboard was developed to visualize the six-year data and to allow for visual comparisons by state and over time. This dashboard is available at (http://ssw.dtn.asu.edu/sextrafficker).

Findings

The research team identified 1,416 persons arrested for sex trafficking of a minor in the United States from 2010 to 2015.

There were sex trafficking of minor arrests in all states except Alaska, Hawaii, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

Other key findings included:

•Three-quarters of the cases involved only minor victims.

•The average age of the sex traffickers of minors was 28.5 years old and theaverage age decreased significantly from 2010 to 2015.

•24.4% of the sex traffickers were female and they were younger than the male sextraffickers.

•75% of the sex traffickers were African American.

•1.2% of the sex traffickers were non-U.S. citizens.

•Nearly one out of five arrests for sex trafficking of a minor involved a person whowas gang involved.

•55.5% of the females arrested were identified in the report as the role of a“bottom” which is the most trusted sex trafficked person by the sex trafficker whomay also be prostituted, may recruit victims, give rules and trainings, and maygive out punishment.

•24% of the arrested sex traffickers had a previous criminal history, the mostcommon previous crime was a violent crime.o4% had a previous arrest for sex trafficking of a minor.

•The minor victims were transported to up to 17 states for the purpose of beingprostituted with the average of 2.7 states.

•The majority of the sex trafficking activities (sex acts) were in hotel rooms.

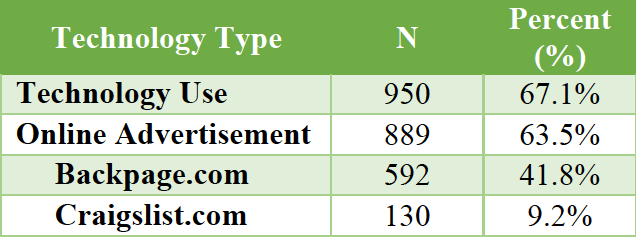

•67.3% of the cases used technology (email, online ads, smart phones) in the sextrafficking activities.oBackpage.com was used by the sex trafficker in 592 cases (41.8%).

•Recruitment tactics focused on runaways; friendship, romance, giving a place to stay to the victim, and promises of money and wealth.

•During recruitment, 15.7% provided their minor victims with drugs and/or alcohol.

•To condition the victims during recruitment, 18% of the sex traffickers sexuallyassaulted and 19.8% physically assaulted their minor victims.

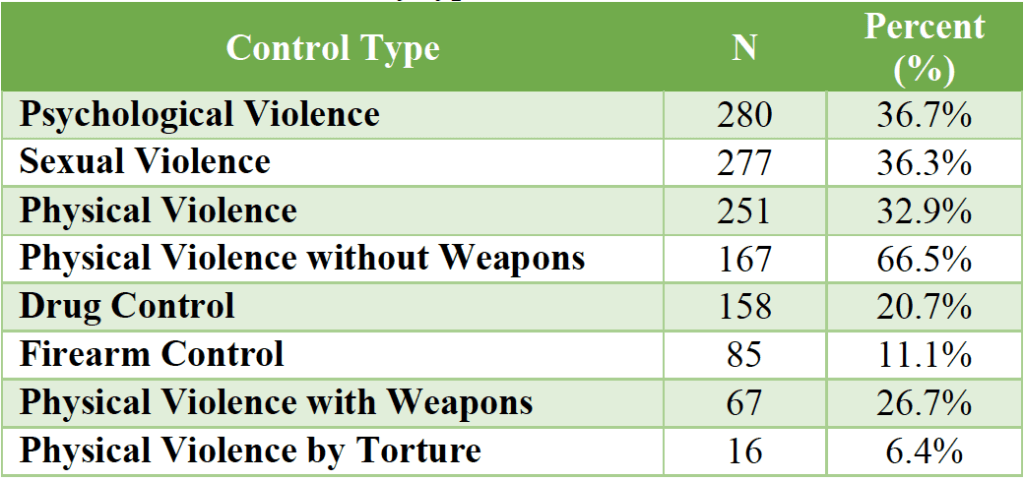

•Victim control tactics included:o36.7% threats of harm and psychological abuse.

•o36.3% sexual violence.

•o26.7% physical assault with a weapon.

•o20.7% drugs to control their minor victim.

•o11.1% threatened the victim with a firearm.

•Details about 941 victims were identified from the 1,416 cases:oFemale (98.9%) with only nine male and one transgender victim.

•The victim’s age at exploitation ranged from age 4 to 17 with an averageage of 15 years old.

•The average age of the victim when their sex trafficker was arrested was15.5 years old.

•45.1% knew their sex trafficker.

•More than half of the victims were runaways.

•Case identification and sex trafficker arrest:oMost cases were reactive cases with a report being made to law enforcement by the victim (18%), their family (10.5%), or an anonymous caller (3.3%).

•20.8% of the cases were identified through police stings.

•Trafficker case resolution:o10.6% of the sex traffickers were denied bond.

•Indicted on an average of 3.78 criminal charges. .

•Convicted on an average of 2.13 criminal charges.

•60.5% of the cases resulted in a plea agreement.

•24.4% of the sex trafficking cases went to trial.

•5% had their charges dropped completely.

•Sentences ranged from no time in prison to life in prison with an average minimum sentence of 13.5 years in prison and 30 sex traffickers were sentenced to life in prison.

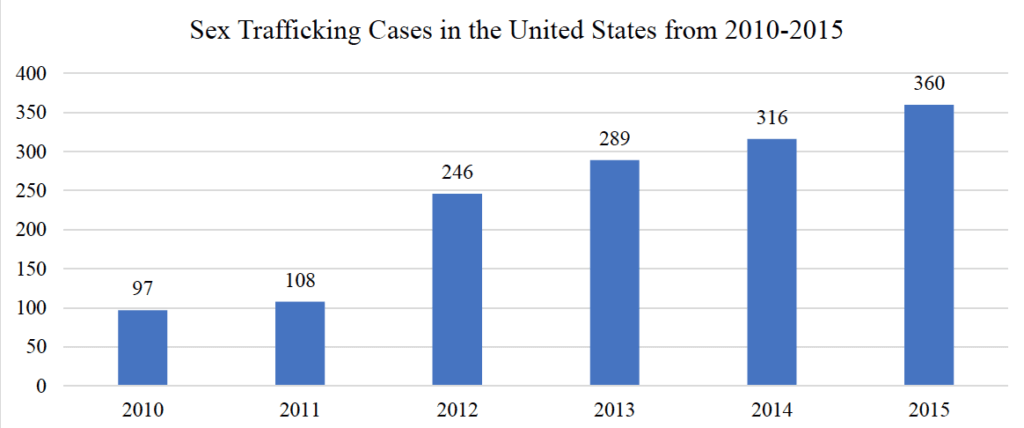

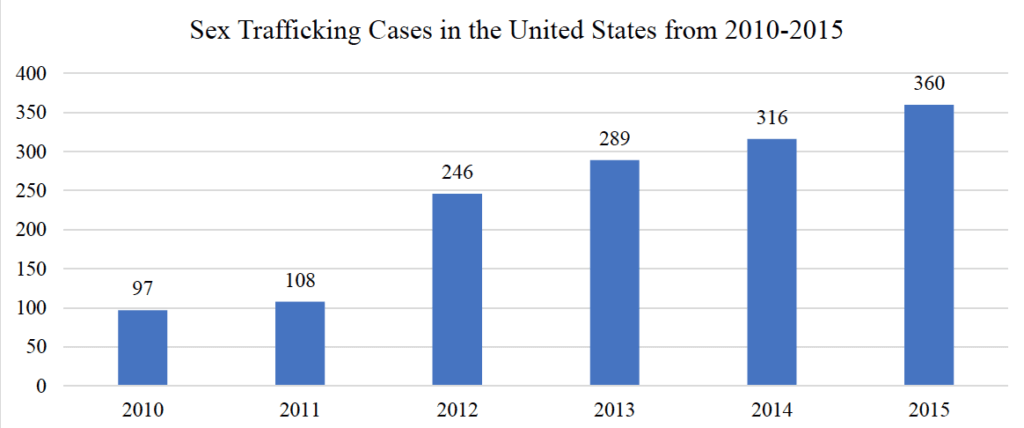

•Trends over the six years (2010 to 2015):oSignificant increase in sex trafficking cases from 97 cases in 2010 to360 cases in 2015.

•Steady increase in female sex trafficker involvement.

•Age of the sex traffickers dropped over time.

•Gang involvement of the sex traffickers dropped over time.

•Sex traffickers were increasingly likely to have a history of a violent crime over time.

•Increase in sex traffickers providing their minor victim with shelter asa recruitment tool.

•Steady increase over the six years of sex traffickers being involved in renting the hotel rooms used in the sex trafficking activity.

•More sex traffickers were found to exclusively victimizing only minor victims over the six years.

Implications

The findings of this study indicate that arrests for the sex trafficking of minors is increasing. These cases are complex and include the use of technology, exploitation of the vulnerabilities of youth in our communities, involve gangs, women, and sex traffickers are persons often known to the victims. There are four states in the U.S. (Alaska, Hawaii, West Virginia, and Wyoming) that have no arrests for this crime. There are unique features of each case which collectively developed a typical profile of a person arrested for sex trafficking of a minor in the U.S.

The increased prominence of female sex traffickers has implications for public perception, as sex traffickers are stereotyped as being only males. The involvement and the unique roles in the sex trafficking activity of the female sex traffickers, as well as their previous sexual exploitation experiences, are necessary next steps to explore and to gain a greater understanding of evolving sex trafficking trends. The majority of the sex traffickers had only minor victims, which indicates a type of ‘specialty’ offender. The level of violence used by the sex traffickers to recruit and sell the minor victims should be considered when law enforcement investigates crimes and during the prosecution of the sex traffickers. Future research and training should be focused on the areas of the country with no or few arrests for sex trafficking of a minor as well as the hospitality and transportation industries, which in most cases were found to interact with a minor sex trafficking victim.

INTRODUCTION

The sex trafficking of minors in the United States has steadily received increasing attention from the public, lawmakers, law enforcement, social service providers, and researchers during the past two decades. Various factors contribute to the commercial sexual exploitation or sex trafficking of a child including community, individual, family and peer-related factors (Williamson & Prior, 2009). Most of the existing research focuses on these factors and vulnerabilities, along with the sex trafficking experiences of sex trafficking victims, and the challenges of exiting the ‘life’ or sex trafficking situation. Few studies have focused exclusively on sex traffickers, and even fewer have focused on the sex traffickers of persons under the age of 18 (minors).

Hargreaves-Cormany, Patterson, and Muirhead (2016) explore the psychopathy of 117 sex traffickers of minors finding that they pose a significant risk to society and fit into aggressive/antisocial and charismatic/manipulative psychopathy categories. Reid (2013) and Kennedy et al. (2007) explore the recruitment techniques of sex traffickers. Reid (2016) focused on cases of juvenile sex trafficking victims and explored sex traffickers’ methods of enmeshment and entrapment. Copley (2014) explored the sociocultural influences on sex traffickers’ techniques. Raphael, Reichert, and Powers (2010) interviewed 100 women and girls in Chicago who had pimps and explored their experiences with violence and coercive control. Williamson and Prior (2009) explored the violence and victimization experiences of 13 child sex trafficking victims including the recruitment and retention actions of their sex traffickers. Kennedy et al. (2007) explored paths of recruitment used by sex traffickers including pretense of love, violence, threats, debt, manipulation, and drug addiction.

Other studies have explored the methods of sex traffickers’ techniques to recruit and sexually exploit their minor and adult victims, including grooming through spending money on them and becoming a trusted person (Kennedy et al., 2007; Reid, 2016), violence (Kennedy et al., 2007; Williamson & Cluse-Tolar, 2002), providing drugs (Parker & Skrmetti, 2012), and a false sense of love and illusions of fantasy (Bracey, 1983; Reid, 2016; Williamson & Cluse-Tolar, 2002). In a larger study about the sex market, Dank et al. (2014) explored the roles of risk management, recruitment methods, and use of violence through interviews of sex traffickers.

Currently, no national database or data collection tool is being used in the United States to collect the arrest of persons for sex trafficking of a minor. Furthermore, no national estimate of how many arrests have been made each year for the sex trafficking of a minor is available. In the federal level data collection on sex trafficking, such as the Uniform Crime Report, sex trafficking reporting is for commercial sex acts, which is a combined arrest number of sex traffickers, prostituted persons, and sex buyers. This study explores the individual characteristics and sex trafficking behaviors that includes a broad sample of sex traffickers of minors over a six-year period from 2010 to 2015. This study is the first study of a national cross-sectional sample of arrested sex traffickers of minors and has implications for local, state and national policy.

Previous Research on the Sex Traffickers of Minors

In a study of 143 convicted sex traffickers, Dank et al. (2014) found that many sex traffickers recognized that sex trafficking a minor was more likely to get them into trouble with the law. Moreover, society is much more concerned with minor sex trafficking victims compared to adult victims. Sex Traffickers also reported that minors were easier to manipulate and control and earned more money in the sex industry than adults. Dank et al. (2014) identified the key method of recruitment the sex traffickers used to find and retain sex trafficking victims was manipulation. Their techniques included using sexual or romantic relationships, mutual dependency, monetizing sex, making promises of a better lifestyle, and using their reputation as a pimp to recruit victims. The types of victims that sex traffickers targeted included women and girls who were economically disadvantaged, drug-dependent, victims of abuse, and lacking in emotional support. The sex traffickers stated that minors, in particular, are easier to manipulate due to emotional immaturity, and easier to control due to a lack of social support since most of the underage victims were runaways. Reid (2016) explored 43 case files of juveniles who had been sex trafficked in Florida. She found that sex traffickers used a combination of techniques to entrap and entangle their juvenile victims into sex trafficking situations other methods were used to keep the victims from escaping. Entrapment and entanglement techniques included flattery and romance, becoming a trusted ally or friend, the normalizing of sex through jokes or having consensual or sexually assaultive sex with their victims, isolating their victims and preying on victims who are naïve to exploitation. Retention techniques were also described by Reid (2016), which include shame or blackmail, loyalty, controlling their phone, money, limiting access to helpers, impregnating, and convincing them that this was what they were meant to do or become. Kennedy et al. (2007) explored the techniques used by sex traffickers to recruit minors and adults into street-level prostitution. She described the methods employed by sex traffickers particularly with adolescent girls including “love, debt, addiction, physical might and authority” (p. 4). Kennedy et al. (2007) suggest that sex traffickers do not just use one technique, but chose from a range of behaviors to recruit and keep their victims in the sex trafficking situation depending on the characteristics of the victim. Study Overview The purpose of this study is to explore the individual characteristics and sex trafficking-related actions and behaviors of sex traffickers of minors during a six-year period in the United States. The goals for the findings of this study are to 1) use the information to develop specific training for law enforcement and prosecutors on characteristics and sex trafficking behaviors of a large sample of sex traffickers, 2) explore the distribution of arrests of sex traffickers of minors in the U.S., 3) identify typologies of arrested sex traffickers of minors, 4) explore patterns of different types of sex traffickers of minors (females, gang-involved, solo offenders), 5) add to the literature regarding the vulnerabilities of minors exploited by the identified sex traffickers, and 5) fill a gap in the knowledge about the scope of arrests of sex traffickers of minors in the United States. 3 Specifically, this study intends to address the following key research questions:

•Does every state in the United States have arrests for sex trafficking of minors? If yes,what were the geographic trends over the six years (2010-2015)?

•What are the individual characteristics of the national sample of sex traffickers of minors regarding gender, age, race, gang involvement, citizenship, occupation and criminal history?

•Do the sex trafficking actions of female sex traffickers differ from the sex trafficking actions of male sex traffickers?

•What recruitment, connection to buyers, and retention techniques were used by the sex traffickers of minors?

•What were the vulnerabilities and risk factors of the minor victims exploited by the sex traffickers to recruit the victims?

•Do gang-related sex trafficker of minor cases differ from non-gang related sex trafficker of minor cases?

•Do solo sex traffickers of minors differ from sex traffickers who worked in groups?

•How were the sex trafficking situations identified by law enforcement? Using descriptive and comparative analysis of the arrests over the six-year period, the study intends to provide valuable information about sex traffickers of minors that can assist with developing prevention and intervention programs.

METHODS

Research Design

This report uses data collected through a structured online search that produced a six-year picture of the arrests in the United States of the specific charge of sex traffickers of minors from 2010 to 2015. The data for this study was collected through a two-step process. The steps include 1) a structured online search for arrests for sex trafficking of minors which resulted in a master list of names and some details of the sex trafficking situation, and 2) a web search of the identified sex trafficker of a minor identified in the arrest report (media, local, state or federal report) to include any follow-up reports, court documents, or police reports.

Participants of this study were persons arrested for sex trafficking of a minor who were identified through a structured online search starting on January 1, 2010, and ending on December 31, 2015. Included in the study were persons that met the search criteria during the period identified and were charged with a sex trafficking crime against a minor (under the age of 18)that occurred in the United States and the U.S. territories and were charged in U.S.jurisdictions. Data was collected for as many cases as could be identified. The Arizona StateUniversity Institutional Review Board approved this study.

This study focused exclusively on sex traffickers of minors, defined as a person who facilitates and/or benefits by receiving something of value for the commercial sexual exploitation of a minor, or attempts to do so. This study purposefully excluded individuals arrested for attempting to purchase or a person who purchased sex from a minor sex trafficking victim.

To be included in this study, an arrest must have been completed for sex trafficking of a minor. The following definitions and exclusion parameters were used to identify sex traffickers for this sample:

Commercial sex: Exchange of any sex acts for an item of value. Item of value: Includes, but is not limited to money, drugs, transportation, food, or shelter.

Facilitating commercial sex: Includes, but is not limited to recruiting another person for commercial sex, providing money for commercial sex-related costs (posting advertisements online, renting hotel rooms, buying condoms, etc.), and providing transportation for someone else to engage in commercial sex.

Exclusion criteria: Sex trafficking of adults only Non-commercial sexual exploitation of a minor Cases in which the defendant offered something of value for sex acts with them, without the intent to offer the minor to others for items of value Production, possession, or distribution of child pornography, unless the conduct was incidental to having the minor engage in sex acts for something of value that the defendant would receive Cases that took place in another country Cases in which all victims were transported into the U.S. from another country

Procedures

The data for this study was collected from web-based media reports found through the Google search engine, electronically filed court documents, and online press releases from government agencies. While each of these source types have their limitations, they also have redeeming qualities that made them suitable for the purposes of this study. Web-based media reports can be used to ensure an extensive search by allowing researchers to gather the most comprehensive sample possible using the available resources. In addition, the information in media reports is based on official reports and statements from law enforcement agencies, as well as interviews from the victims or perpetrators involved. However, since the media must focus on gaining readers to generate income, they may underreport trafficking situations that are not dramatic or leave out information considered uninteresting. Electronically filed court documents tend to be sources that provide the most complete portrayal of a trafficking situation and come from trustworthy sources. However, they are not often available since many courts do not file their records online and non-redacted documents are not available to the public when the victim is a minor. Press releases from government agencies, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) or the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), are frequently available and come from trustworthy sources, but they can be to-the-point and lacking in detailed information. 5 Data Analysis Researchers entered the data into an SPSS database, which was used to collate, code, and analyze the data. T-tests, ANOVA chi-square analysis were used to explore the sex trafficker and victim characteristics and differences as well as changes over the six-year data collection period.

RESULTS

Individual Characteristics

There were 1,416 sex traffickers of minors arrested from 2010 to 2015 in the United States. There was a steady increase from 2010 to 2015. Figure 1. The number of media reported sex trafficking cases in the U.S. over a 5-year period.

The gender of the sex traffickers of minors were identified as males (n =1067, 75.4%), female (n =346, 24.4%), and transgender (n=1, 0.1%). Figure 2. Gender distribution of the sex traffickers.

The race of the sex traffickers was identified for only 731 (51.6%) of the cases with 71.7% (n=524) African American, 20.5% (n =150) Caucasian, 3.7% (n =53) Hispanic, 0.2% (n=3) Pacific Islander/Asian, and Other, 0.1% (n =1).

Figure 3. Race distribution of the sex traffickers.

The sex traffickers of minors age when arrested ranged from 15 to 70 years old (M =28.5, SD = 8.54). Thirteen of the sex traffickers were under age 18. The female sex traffickers were significantly younger than the male sex traffickers, with an average age of 26.34 years versus an average age of 29.2 years for male sex traffickers (t (1364) = 5.405, p < .001). Seventeen (1.2%) of the sex traffickers of minors were non-U.S. Citizens. Eight were undocumented foreign nationals, and nine were non-citizens with U.S. visas.

Victim Information

Many cases had an estimation of the number of juvenile victims with a total of 1,804 minor victims identified with detailed information only available for 941 victims. Of the known cases, the majority of victims were female (N= 931, 98.9%), followed by male victims (n = 9, 1%), and one identified as transgender (n = 1, 0.1%). Victims were an average age of 15.03 (SD = 1.84) years old when their sex traffickers first exploited them, with the youngest at 4 years old and the oldest at 17 years old. Victims were sex trafficked for an average of 154.4 days ranging from one day to eleven years. The minor sex trafficking victims were an average age of 15.51 (SD = 1.714) years old when their sex traffickers were arrested, with the youngest victim at 4 years old and the oldest at 23 when their trafficker was arrested.

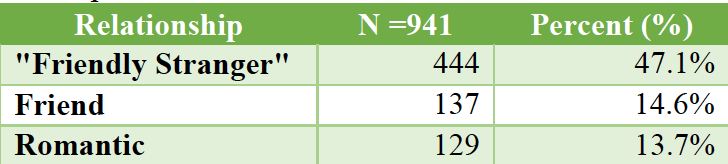

More than two thirds of the victims were runaways (n = 631, 67.1%), and 54.9% had no prior relationship to their sex traffickers (n = 517). Where the victim lived prior to being sex trafficked was only available for 607 victims. Of the known cases, victims lived at home (n = 478, 78.7%), group homes (n = 81, 13.3%), foster care (n = 39, 6.4%), were homeless (n = 28, 4.6%), and in juvenile detention (n = 14, 2.3%).

Table 1. Victim relationship to sex trafficker.

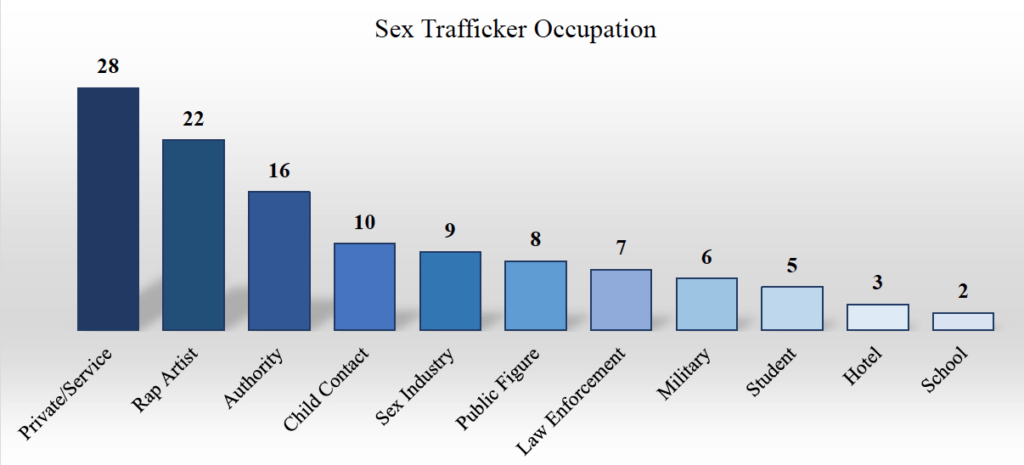

Occupations of the Sex Traffickers of Minors

Researchers were able to gather information the occupations of only 88 sex traffickers. These occupations include only legal and legitimate work and do not include illegal sources of income. Some sex traffickers (n = 28) worked in private or service industries as truck or taxi drivers, repair people, or owners of small businesses. The next most prominent occupation was the music industry, with 22 sex traffickers who identified as rap artists. There were also sex traffickers who held positions of authority (n = 16), such as law enforcement officers, security guards, and counselors. Ten sex traffickers had jobs that gave them regular access to minors, such as jobs at elementary schools or at group homes for troubled youth, including one juvenile probation officer. Nine sex traffickers already worked in the legal sex industry, either as dancers or as managers of strip clubs. Other sex traffickers were public figures (n = 8), law enforcement officers (n = 7), in the military (n = 6), students (n = 5), or worked at hotels (n = 3) or schools (n = 2).

Figure 4. Reported Occupations of Sex Traffickers.

Arrest Locations

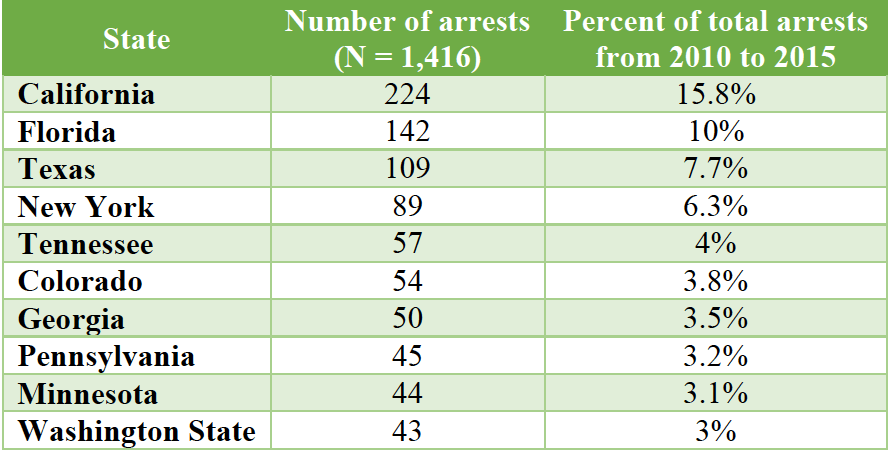

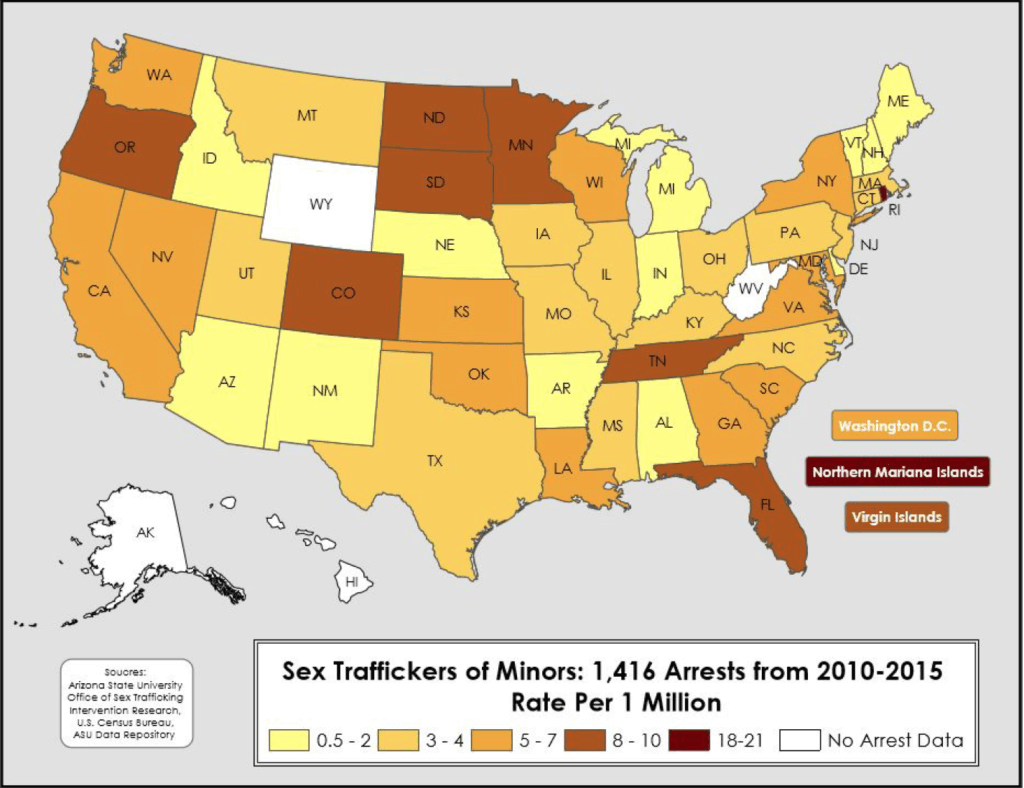

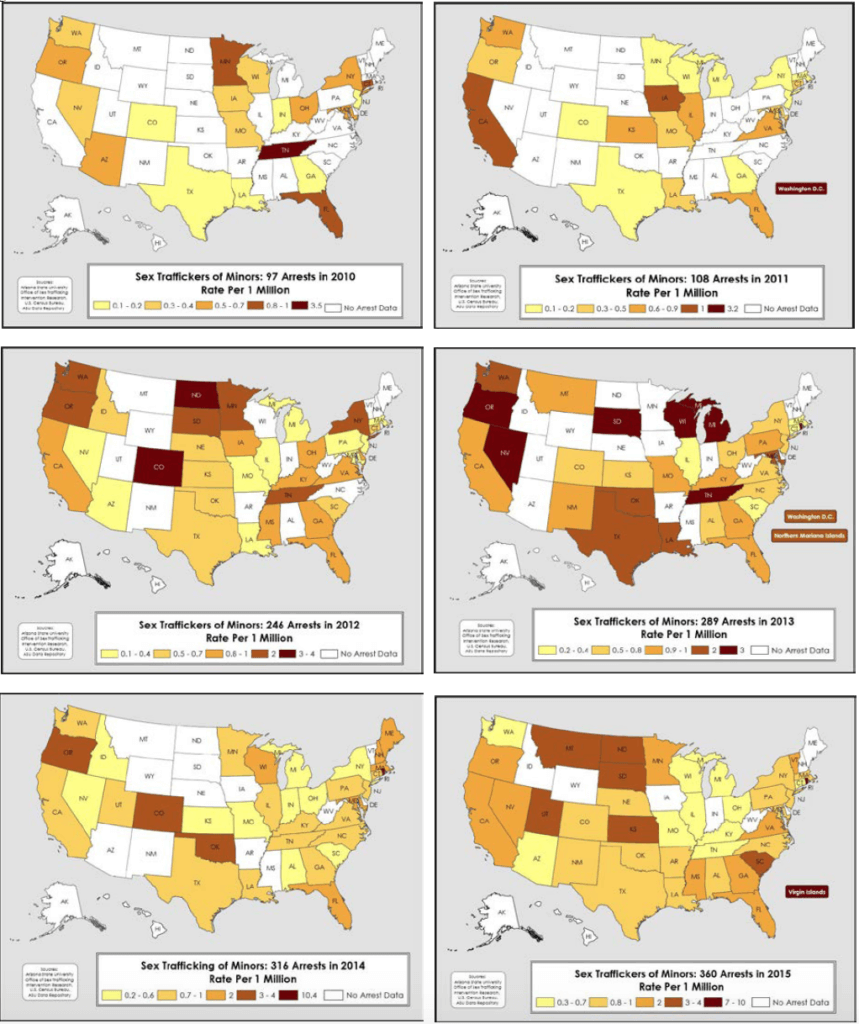

The 1,416 individuals arrested for sex trafficking of a minor were found in reports and cases filed in 46 states in the United States along with two U.S. territories and Washington D.C. The states with the highest number of arrests of sex traffickers of minors are listed in Table 2 and Map 1 is a graphic view of the arrest frequency by population in each state.

Table 2. States with the highest number of arrests for sex trafficking of minors in the U.S. from 2010 to 2015.

No arrest reports of sex traffickers of minors during the six-year study period were in Alaska, Hawaii, West Virginia, and Wyoming. Twelve states had fewer than five arrests and six states had less than ten arrests during the six years.

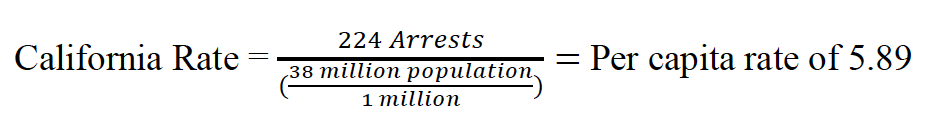

Although the number of arrests per state is important to know, the rate of arrests per state shows a more accurate picture. Populations with more people, like California for example, are almost certainly going to have more instances of crime simply because there are more people to partake in the crime and more target victims within a large population. Per capita rate is a tool used to even the playing field when comparing areas with vastly different populations. For Figure 5, the rate reveals how many instances of arrest for every 1 million people. There are roughly 38 million people in California with 224 arrests.

This calculation shows that for every 1 million people in California there are approximately 6 arrests of sex traffickers of minors.

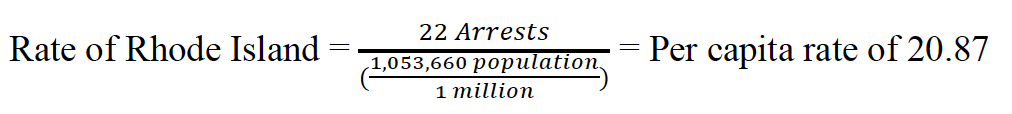

When compared to a small state with a lower population, such as Rhode Island, the importance of rate is very apparent. Rhode Island has a population of slightly over 1 million with 22 arrests.

This calculation displays that for every 1 million people in Rhode Island there are approximately 21 arrests of sex traffickers of minors. Although Rhode Island has a much lower number of arrests at 22 compared to California’s 224 arrests, their rates show that Rhode Island has a much higher instance of arrests than California.

Figure 5. Map of all arrests for the sex trafficking of a minor in the U.S. from 2010-2015.

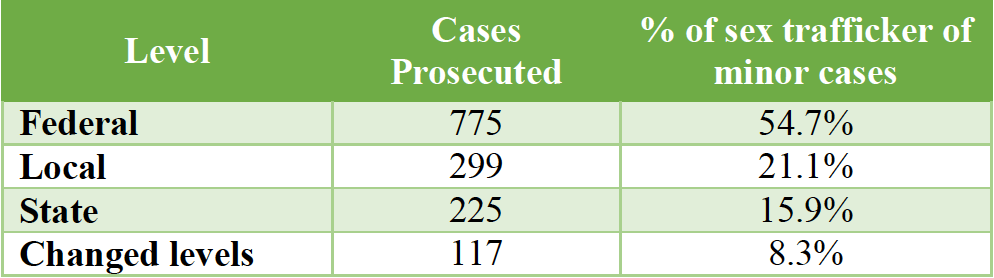

Prosecution Level

The majority of the prosecutions in the arrests of the sex traffickers of minors were at a federal level (n = 775, 59.7%). There were 117 cases that moved from one level (local, state, federal) to another level after the arrest was filed.

Table 3. Number of prosecuted sex trafficker cases, by level.

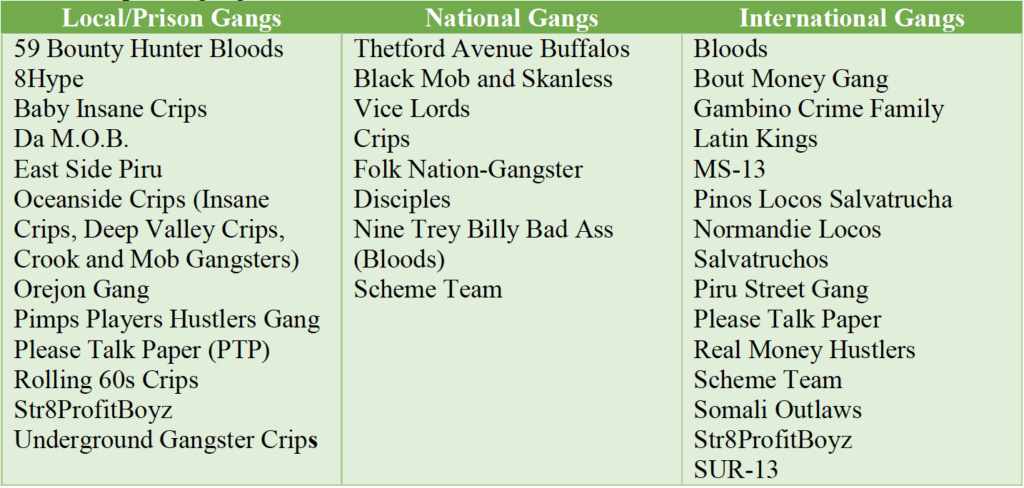

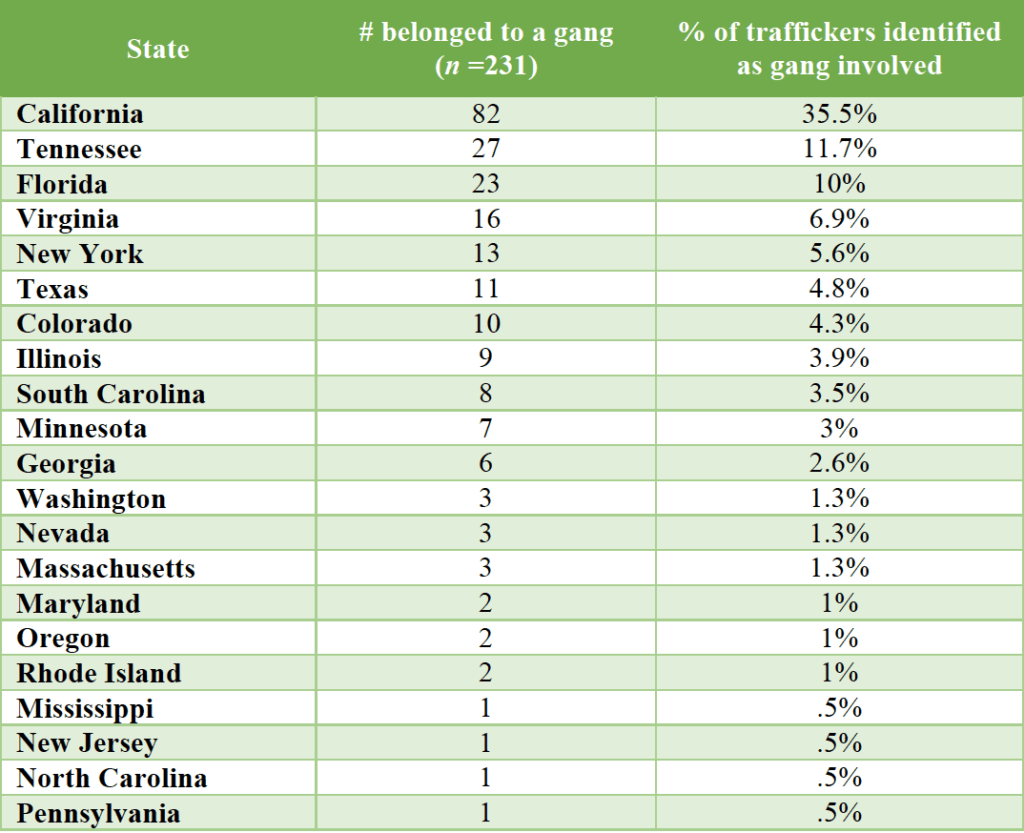

Sex Trafficker Gang Involvement

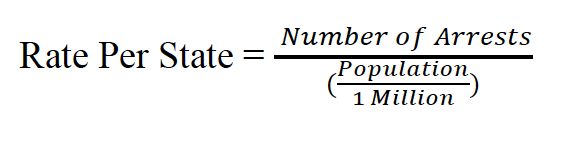

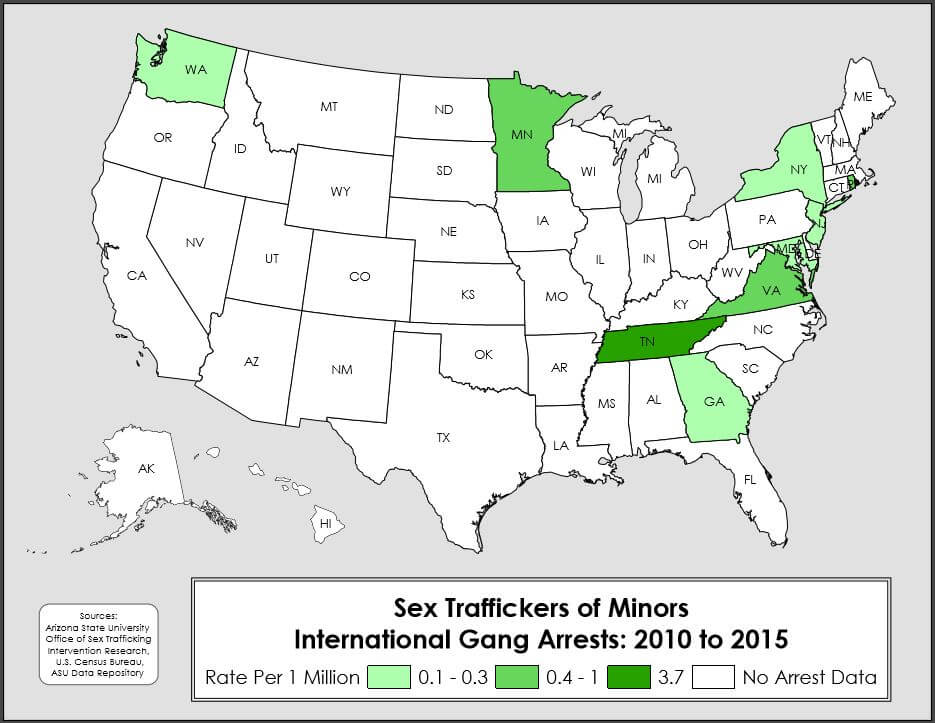

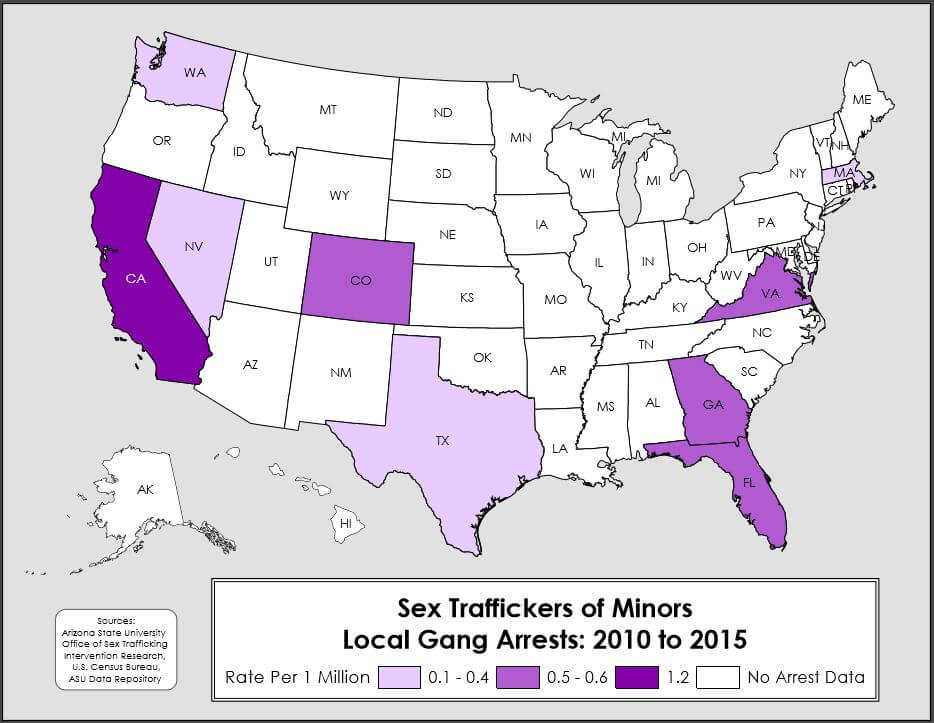

Gang affiliation of the sex trafficker was identified in 231 cases (19.1%) with 50 (21.6%) of the 231 gang affiliated sex traffickers identifying as members of international gangs.

Table 4. Reported gang affiliations of sex traffickers

Table 5. Reported gang involvement of sex traffickers, by state.

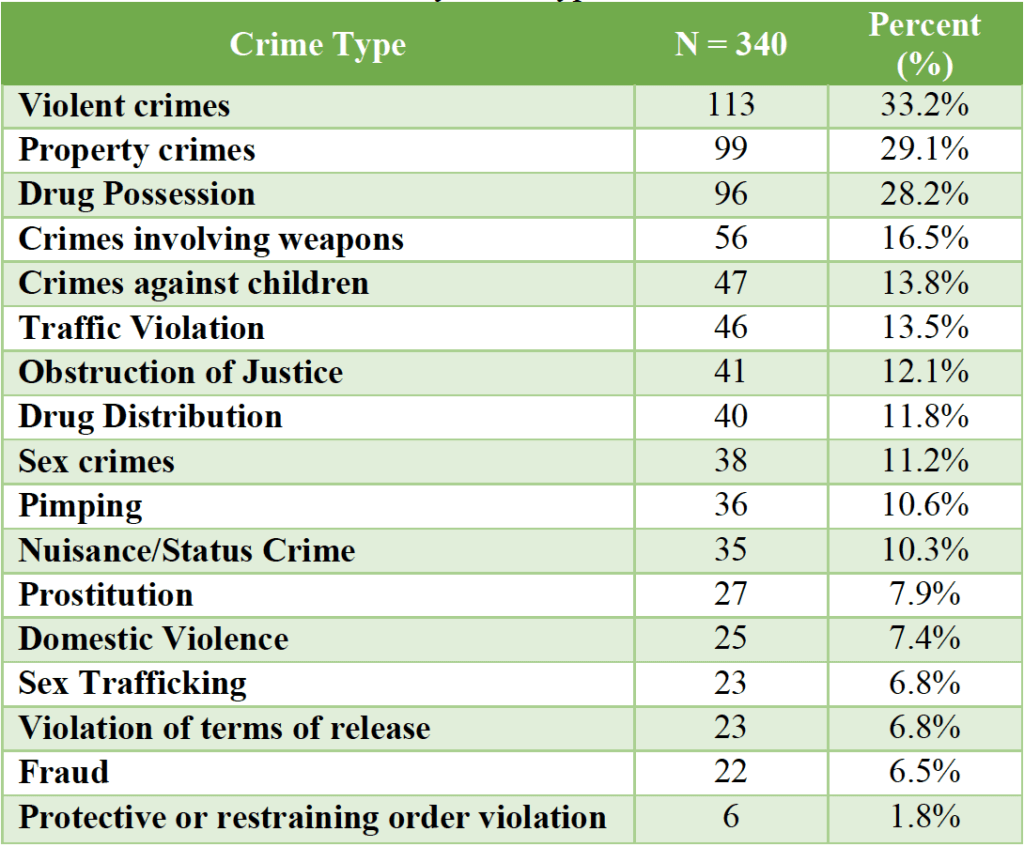

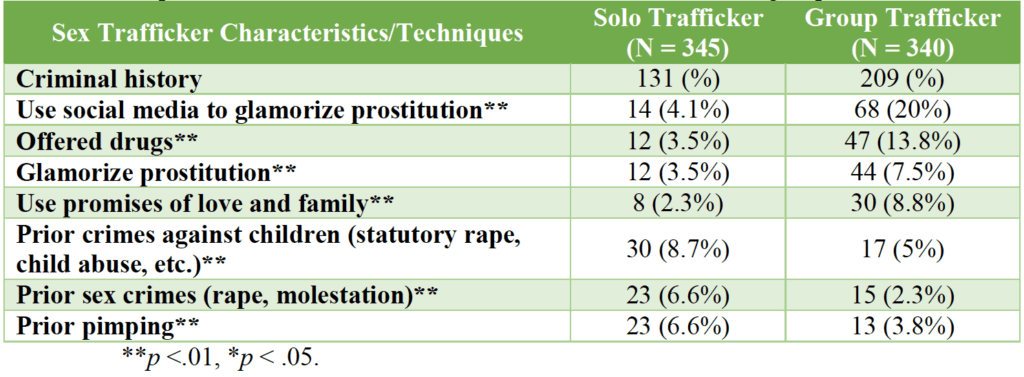

Previous Criminal History

Twenty-four percent (n =340) of the sex traffickers of minors were found to have a criminal history, of those, 35 (10.3%) were gang members. Nearly 4% of the sex traffickers of minors (n =53) were found to have a previous arrest for the sex trafficking of a minor. Thirty (2.1%) were registered sex offenders from a prior criminal conviction. The most common type of crime that had been previously committed by the sex traffickers was a violent crime against people (n = 113), such as assault, battery, and robbery. The second most common type of previous arrest was for a property crime (n = 99), including crimes such as burglary, theft, or trespassing. Drug possession (n = 96) was the third most common type of crime committed by sex traffickers. Other common crimes committed by the sex traffickers of minors included crimes involving weapons (n = 56), crimes against children (n = 47), traffic violations (n = 46), obstruction of justice (n = 41), drug distribution (n = 40), sex crimes (n = 38), pimping (n = 36), and nuisance and status crimes (n = 35). Other less common crimes included prostitution (n = 27), domestic violence (n = 25), sex trafficking (n = 23), violation of terms of release (n = 23), fraud (n = 22), and court order violations (n = 6). Previous charges of pimping or promoting prostitution and sex trafficking (combined) were found in the criminal histories of 4.2% of the sex traffickers of minors.

Table 6. Sex trafficker criminal histories, by crime type.

The found reports included some details about the roles of the sex traffickers in the sex trafficking situations and 185 (53.4%) of the female sex traffickers were identified as the “bottom bitch,” sometimes referred to as the “bottom,” who is considered to be the trafficker’s has most trusted worker. Often, the bottom is the trafficker’s highest earner and is the one who has been with the trafficker the longest (Weinkauf, 2010). The bottom may become responsible for recruiting other individuals, for grooming and teaching others the “rules of the game,” for posting ads for the other individuals, for handling money, and may even dole out punishments. Females identified as ‘bottoms’ were found to be significantly younger than their trafficker counterparts, with an average age of 24.2 years old versus 29.24 years for non-bottoms (t (1302) =7.526, p = .001).

Actions of the Sex Traffickers

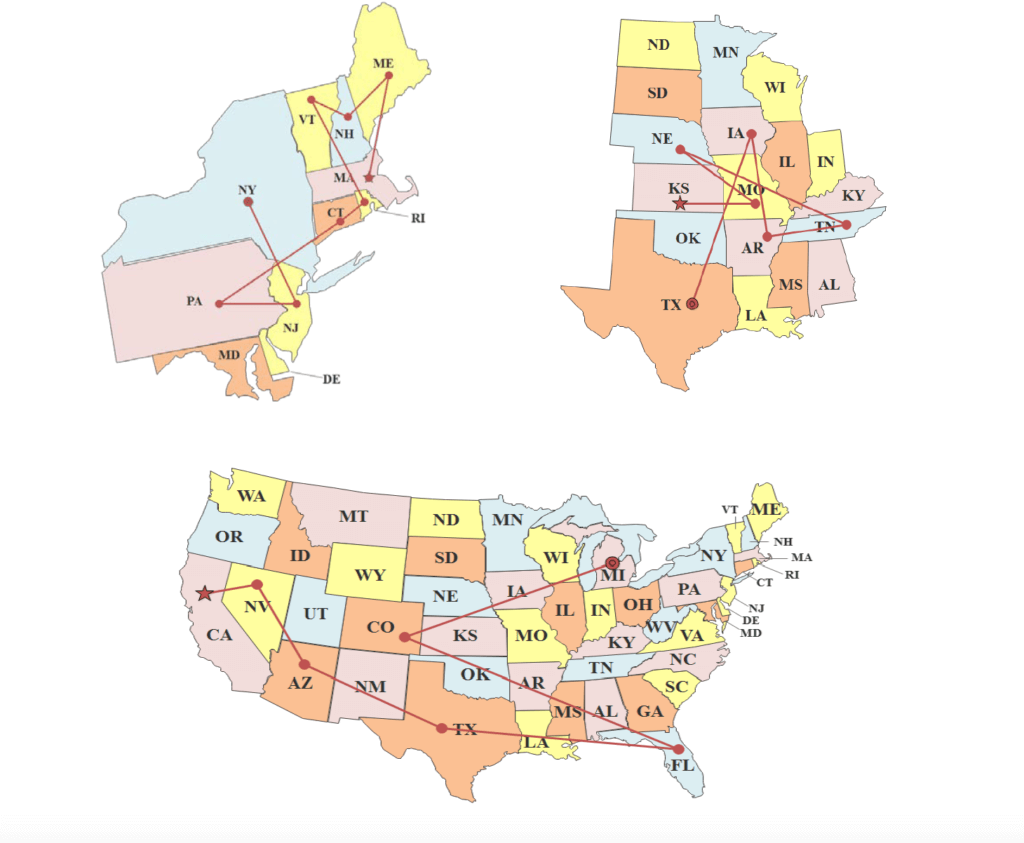

Transportation of the Victims

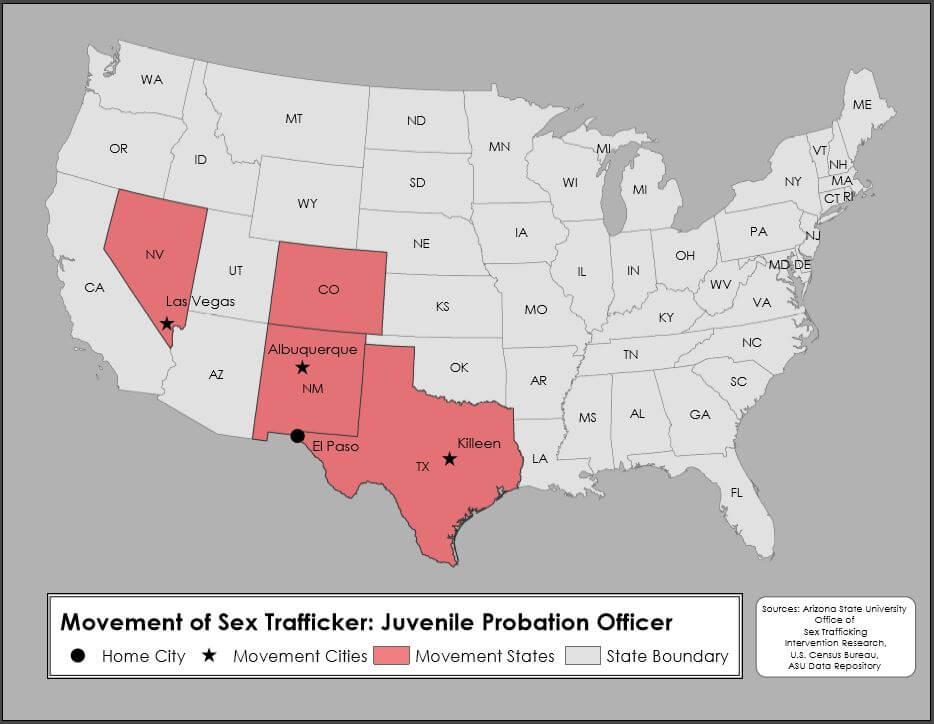

In 249 (32.6%) of the cases, the sex trafficker crossed state lines with the minor victim. The sex trafficker used all types of transportation (auto, bus, trucks, airplanes, trains). Sex traffickers moved their minor victims to up to 17 states within the United States to prostitute them with an average of traveling to 2.76 states. Some examples of travel patterns are: Figure 6. Examples of sex trafficker travel patterns.

Although there were no arrests for sex trafficking found in Alaska, Hawaii, West Virginia, and Wyoming, sex traffickers had reportedly traveled to and sold their victims in these states.

Recruitment Tactics

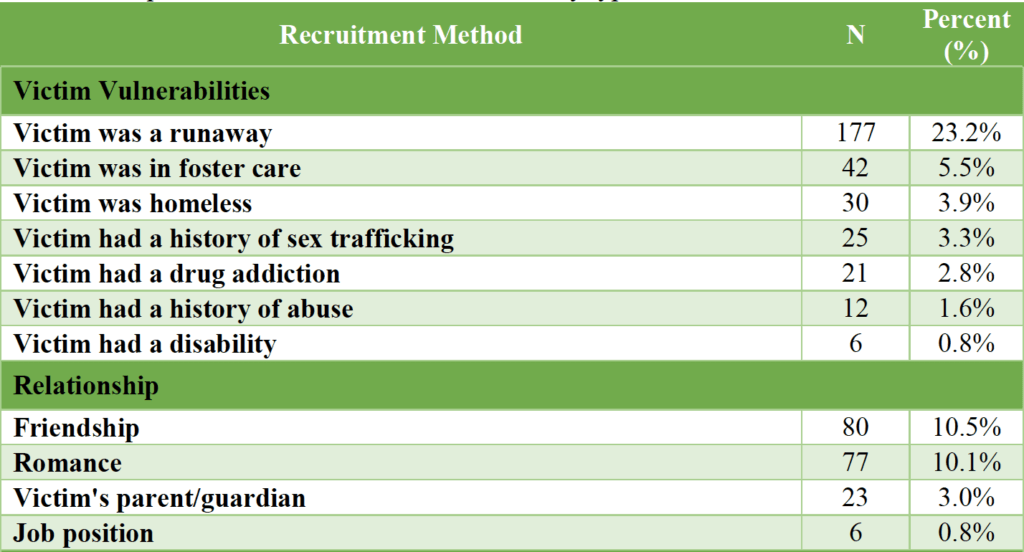

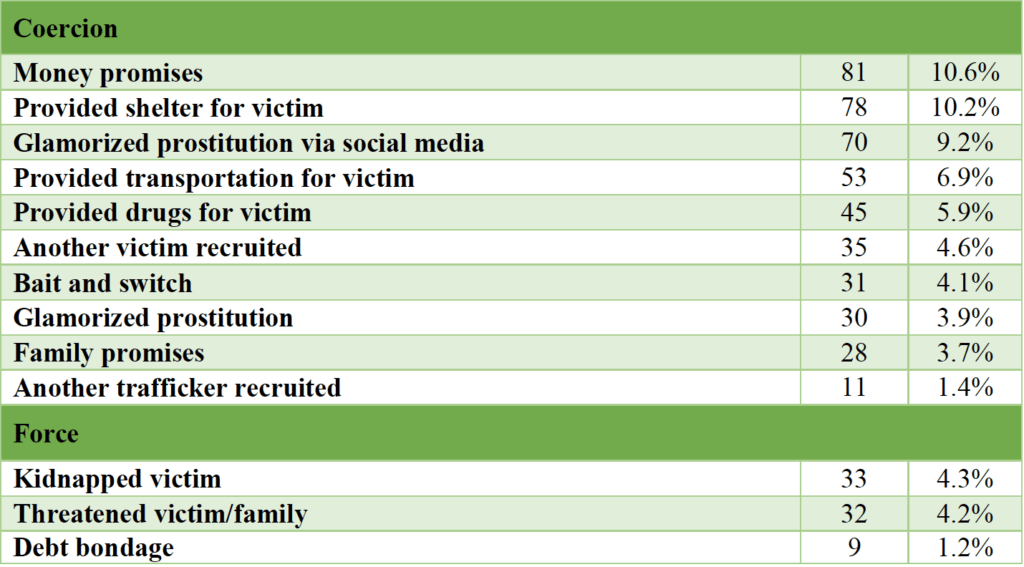

Sex traffickers used a number of different tactics to find and recruit their victims. In almost one-quarter of the cases (n = 177, 23.2%), the sex traffickers had victims who were runaways. They used promises of money and wealth (n = 81, 10.6%) and offered victims a place to stay (n = 78, 10.2%), used friendships (n = 80, 10.5%), and romantic relationships (n = 77, 10.1%) to recruit their victims.

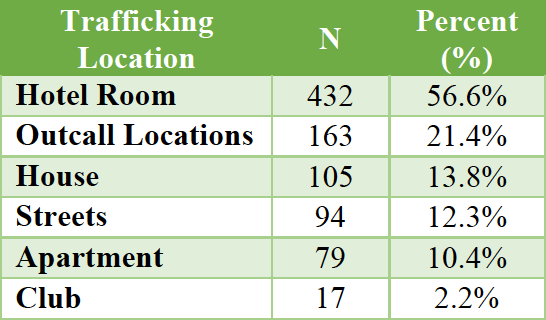

Trafficking Tactics and Actions

Nearly a third (31.7%, n =242) of the sex traffickers also had an adult sex trafficking victim at the time they sex trafficked the minor. The victims were trafficked from a variety of locations. The most common venue was hotel rooms, with more than half of the cases (n = 432, 56.6%) using hotel rooms as a trafficking location. The second most common were outcall locations (n = 163, 21.4%), where victims were taken to buyers’ homes or locations of their choosing. Victims trafficked on the streets was less common (n = 94, 12.3%), as was trafficking from houses (n= 105, 13.8%), apartments (n = 79, 10.4%), and clubs (n= 17, 2.2%).

Table 7. Sex trafficking venues.

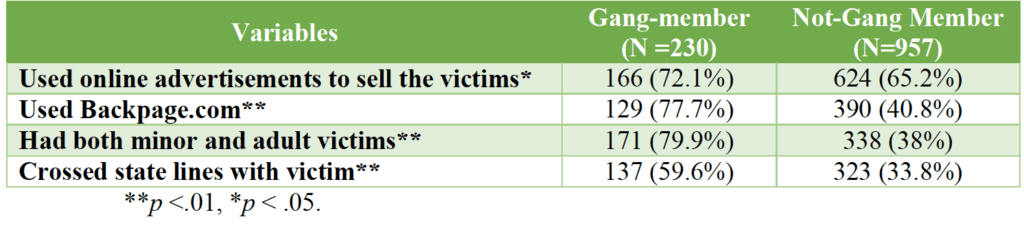

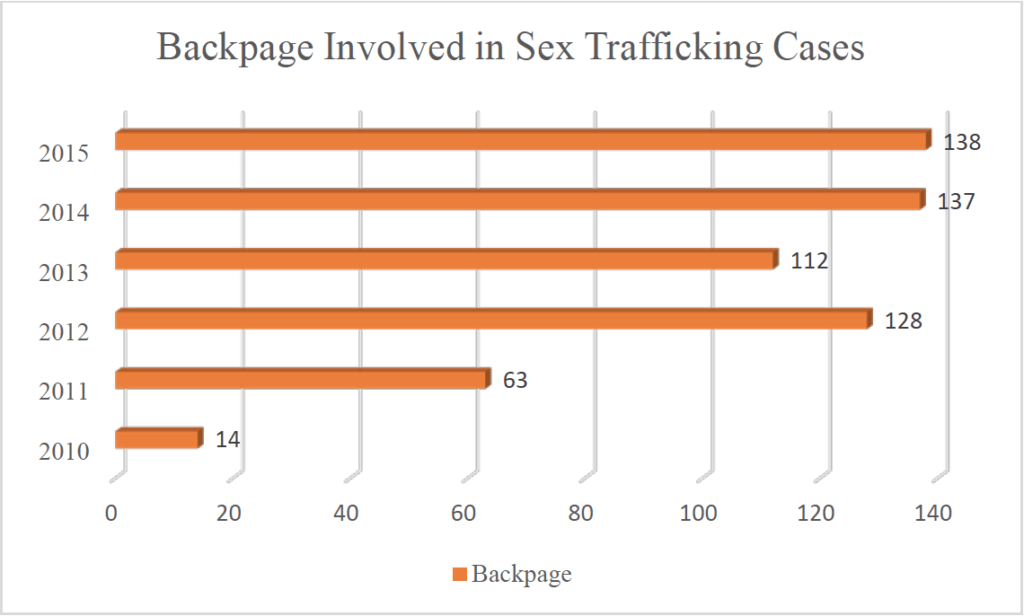

Technology was used during the underage victim’s exploitation in more than two-thirds of cases (n = 950, 67.1%), either by advertising victims online, or by providing a cell phone to the victim. Online advertisements were used in nearly two thirds of the cases (n = 889, 63.5%). The website Backpage.com was specifically used in more than one-third of these cases (n = 592, 41.8%), although the name of the advertising website was not always provided in reports, so the incidence rate may have been higher. Craigslist was used in only a small amount of cases (n = 130, 9.2%), likely due to their ban on escort advertisements on their website.

Technology was used during the underage victim’s exploitation in more than two-thirds of cases (n = 950, 67.1%), either by advertising victims online, or by providing a cell phone to the victim. Online advertisements were used in nearly two thirds of the cases (n = 889, 63.5%). The website Backpage.com was specifically used in more than one-third of these cases (n = 592, 41.8%), although the name of the advertising website was not always provided in reports, so the incidence rate may have been higher. Craigslist was used in only a small amount of cases (n = 130, 9.2%), likely due to their ban on escort advertisements on their website.

Table 8. Technology used in sex trafficking exploitation.

Victim Control Tactics

The sex traffickers used different tactics to control their minor victims, from providing drugs to physical violence and threats. Drugs were involved in 218 cases (28.6%) and were used specifically to control victims in 158 cases (20.7%). Firearms were also involved in one out of 15 every ten cases (n = 85, 11.1%) and were used to intimidate victims. Physical violence, such as punching, kicking, hitting with weapons, and torture, was used in almost one-third of cases (n = 251, 32.9%). Out of these cases physical violence without weapons, like slapping or kicking, was the most prevalent (N = 167, 66.5%). Physical violence with weapons, such as hitting with an object or use of a knife, was less prevalent (n = 67, 26.7%), and torture was the least prevalent type of violence (n = 16, 6.4%). Sexual violence against the victims, which includes any sexual activity with minors or nonconsensual sexual activity with minors or adults was prevalent in 36.3% of cases (n = 277). Psychological violence, such as threats against the victim or their family, was also found in more than a third of the cases (n = 280, 36.7%).

Table 10. Sex trafficker control tactics, by type.

Female Sex Traffickers of Minors

Female sex traffickers were more likely to be arrested in a case that targeted minor victims who are drug addicted (χ2 (1, N = 677) = 4.262, p = .04), needed a place to stay (χ2 (1, N = 689) = 12.732, p = .001), and/or were runaways (χ2 (1, N = 720) = 5.082, p = .017) than male sex traffickers. Females were more likely to be arrested in a case in which the trafficker was a guardian or caretaker to the minor victim (χ2 (1, N = 682) = 34.9, p = .001) when compared with male sex traffickers. The female sex traffickers were significantly more likely to have a prior prostitution charge when compared to the male sex traffickers (χ2 (1, N = 151) = 27.05, p = .001). Female sex traffickers were significantly less likely to be involved in cases where sexual violence was perpetrated against the victim when compared with male sex traffickers (χ2 (1, N = 1140) = 47.218, p = .001).

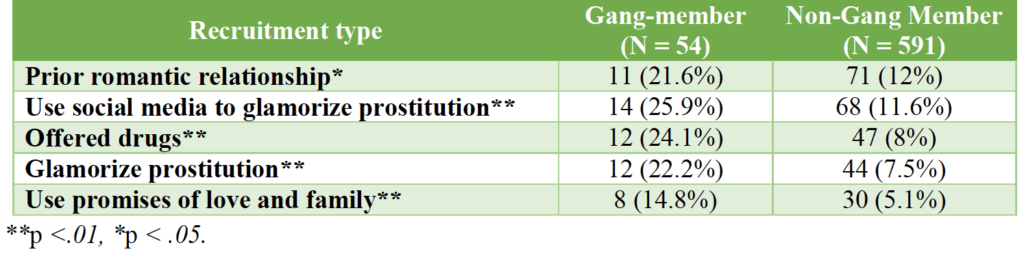

Gang Involved Sex Trafficking Cases vs. Non-Gang Involved

Child sex trafficking victims of sex traffickers who were affiliated with a gang were significantly younger (14.6 years old) when compared to sex traffickers who were not gang members (15.2 years old) (t (717) = 3.5, p < .001). Child sex trafficking victims of gang affiliated sex traffickers were more likely to be addicted to drugs when they were recruited (χ2 (1, N = 636) = 12.42, p = .003), in foster care (χ2 (1, N = 635) = 15.879, p = .001), or homeless (χ2 (1, N = 636) = 5.576, p = .027) than sex traffickers not affiliated with a gang. Child sex trafficking victims of gang affiliated sex traffickers were more likely to have a previous history of sex trafficking victimization (χ2 (1, N = 635) = 18.428, p = .001).

Table 11. Comparison of sex trafficker recruitment tactics, gang member vs. non-gang member.

Several characteristics were compared between gang- involved versus non-gang involved sex traffickers of minors to explore if there was a significant difference in sex trafficker travel tactics, age of victims, and use of technology. Gang involved sex traffickers were more likely to use online advertisements to sell their victims and more than three quarters of the gang-involved cases used Backpage.com to advertise their victims online. Gang-involved sex traffickers were more likely to have both adult and minor victims (79.9%) compared to non-gang involved sex traffickers (38%). Gang involved sex traffickers were also more likely than non-gang involved sex traffickers to transport a victim across state lines for the purpose of prostitution.

Table 12. Comparison of sex trafficker exploitation tactics for gang involved vs. non-gang involved.

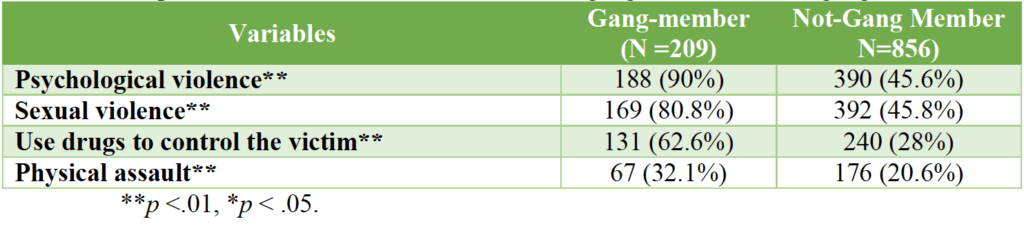

Level of Violence by Gang Involved vs. Non-Gang Involved Sex Traffickers

Case information about violence and gang membership of the sex traffickers was available for 1065 (75.2%) of the sex traffickers with significant differences found. Gang-involved sex trafficker cases were more likely to use sexual and psychological violence and use drugs to control their victims.

Table 13. Comparison of sex trafficker use of violence, gang member vs. non-gang member.

Mapping Gang Involvement in Sex Trafficking of Minors

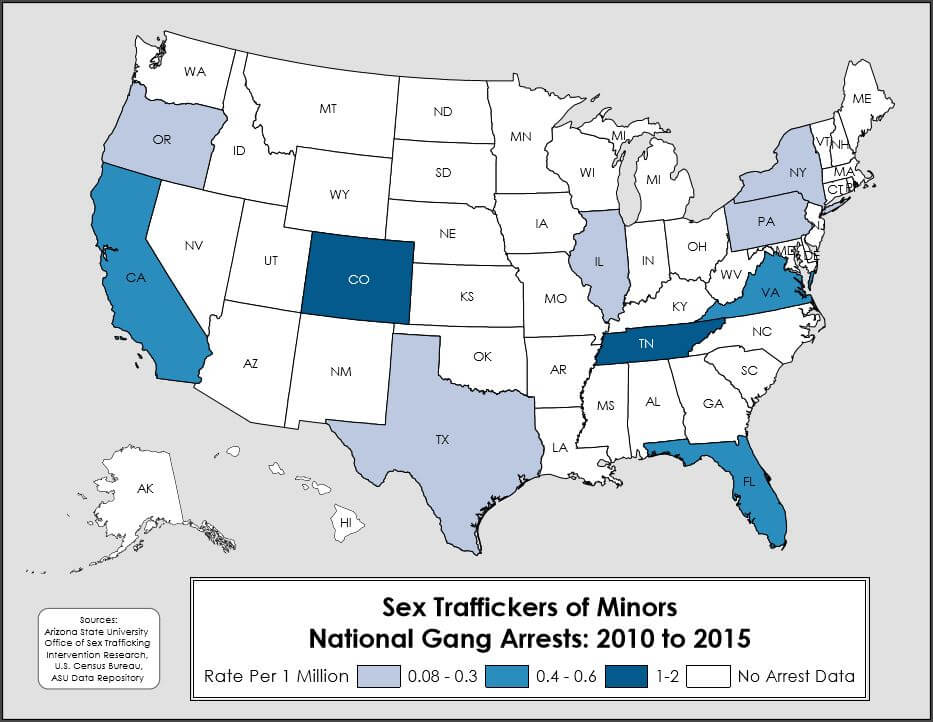

The arrest data collected was initially linked to zip code data. The data was aggregated to the state level because the total number of arrests (1,416) in comparison to the total number of zip codes within the entire United States (over 30,000) was minimal. Aggregating the data to the state level allowed for clear representation using choropleth maps by state using ArcGIS software. The shapefiles, including the boundaries of both the states and their corresponding zip codes, were obtained from the Arizona State University Data Repository. Jenks Natural Breaks was the selected classification method and the rate of each year map, 2010 through 2015, was calculated using the one year American Community Survey Population Estimate provided by the U.S. Census Bureau (n.d.)

The map spanning all six years utilized the five year American Community Survey Population Estimate for 2015 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). The population for the Virgin Islands and Northern Mariana Islands were taken from their government websites using 2015 population estimates, respectively (Northern Mariana Islands, n.d.; Virgin Islands, n.d.). To procure the rate, the population of each state was divided by one million and the total number of arrests within each state was then divided by this number. The map spanning all six years utilized the five year American Community Survey Population Estimate for 2015 (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.). The population for the Virgin Islands (n.d.) and Northern Mariana Islands (n.d.) were taken from their government websites using 2015 population estimates, respectively. To procure the rate, the population of each state was divided by one million and the total number of arrests within each state was then divided by this number.

Figure 7. Map of all gang-related arrests for sex trafficking of minors 2010-2015.

Gang Maps

Gang data was broken up into three separate categories including Local Gangs, National Gangs, and International Gangs. The Local Gang category included sex trafficker arrests of gang members who operate on a local level within one state. The National Gang category included members of the same gang organization being arrested in two or more states and the International Gang category included gang members linked to internationally known crime organizations. The cities of movement were placed using a Geo Locater on ArcGIS Online. The states of movement were highlighted to show where the trafficking occurred.

For the breakdown of each category, the gang arrest data was aggregated to the state level and the Jenks Natural Breaks classification method was utilized. Choropleth maps were produced showing the rate of gang affiliated sex trafficking arrests within each state using ArcGIS software. The rate was derived from the population of each state divided by one million and the total number of arrests within each state divided by this number.

The general distribution of gang activity is largely located in coastal states or states located along the national borders. Apart from Colorado, Tennessee, Nevada, and Illinois, every state within this map is touching either the Canadian or Mexican border or the Eastern or Western coastal boundary. The International Gang category was represented in ten different states with the highest rate located in Tennessee. The International Gang data shows a distribution toward the east coast. It also includes periphery states of Washington and Minnesota both of which are located along the national border. With the exception of Tennessee, every international arrest is located within a state that touches a coastal boundary or the Canadian border. This distribution of international gang activity is understandable considering most international gangs operating within the states are “franchise” divisions of stronger international gangs located outside the United States. These gangs are more likely to operate predominately in coastal states or states close to borders as opposed to interior states for sheer convenience of location. The states along the east coast are also smaller in area allowing for quicker movement across state lines.

Figure 8. Map of international gang-related arrests for sex trafficking of a minor.

Figure 9. Map of national gang-related arrests for sex trafficking of a minor.

Figure 10. Map of local gang-related arrests for sex trafficking of a minor.

Case studies: Examples of movement of sex trafficking victims

Case Study 1:

Between May 2012 and March 2013, a juvenile probation officer and former NCAA football player from a city in Texas used his job to lure girls into the sex trade. He used force, fraud, and coercion to compel his victims to have sex for money. On January 17, 2014, the juvenile probation officer was arrested and charged with one count of sex trafficking and one count of sex trafficking of a minor. The trafficker recruited two underage victims through his job. One of the 15-year-old victims reported that although he was not violent toward her, the trafficker enticed, transported, and knowingly forced the underage girl to engage in prostitution to benefit him financially. Five other men associated with this case were also arrested and charged with forcing their minor victims to engage in sexual activities for money. The six men arrested were a part of the Folk Nation/Gangster Disciples, a local street gang, which had a trafficking ring where they moved girls and women between four states: Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Texas. Although the trafficker pled not guilty, he was found guilty in 2015 and convicted of conspiracy to commit sex trafficking and sex trafficking of children. He was sentenced to 216 months in federal prison for his role in the sex trafficking ring. In addition to prison time, the trafficker must also pay $2,500 in court fees and $200 to a victim’s compensation fund. He must also participate in a sex offender treatment program and parenting classes. After completing his sentence, the trafficker must serve 120 months of supervised release. The investigation for this case was conducted by the ACTeam (Anti-Trafficking Coordination Team) comprised of personnel from Homeland Security Investigations, Federal Bureau of Investigations, and U.S. Department of Labor together with the local Police Department Gang Unit and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms and Explosives.

Juvenile probation officers go through extensive background checks and this trafficker, before being arrested for sex trafficking, only had traffic violations on his record. By nature of his job, the trafficker used his place of authority and ability to encounter underage girls to benefit the gang-related sex trafficking ring.

Figure 11. Case study 1- Map of victim movement by sex trafficker.

Case Study 2:

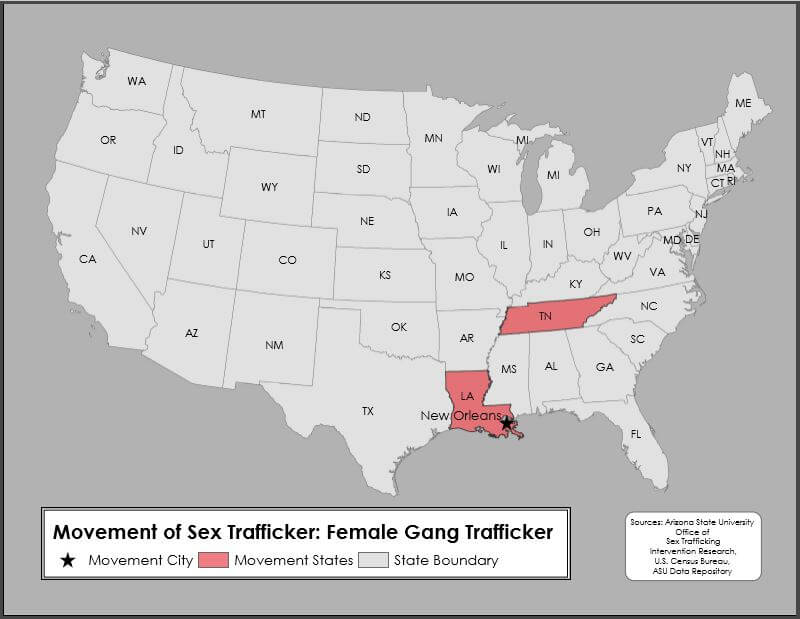

In 2012, a 19-year-old female transported four 15-year-old girls and one 18-year-old within Tennessee and from Tennessee to New Orleans, Louisiana to engage in prostitution. A mother of two young children, a 4-year-old and 9-month-old, the trafficker was a high-ranking member and head of all the girls in the Piru Street gang. One of the minor girls testified that she met the trafficker in 2012 during an initiation for the street gang. The trafficker told the minor girl that she could live with her to attend the school she wanted to go to and that she could make some real money by having sex for money. The trafficker made false promises to all the minor girls promising that money they earned could pay for school supplies and clothes. The trafficker used force and threats of force to control her victims and took all the money and spent it on herself. The trafficker was caught with the four juveniles and one adult when she was arrested in 2012 for driving a stolen car. The victims reported the trafficker to the police. One of the juvenile victims testified that she witnessed the trafficker drag a woman by her hair and beat her when she “stopped liking” her work and “didn’t want to walk” the streets anymore. The minor also reported threatening texts sent to her from the trafficker, which were used as probable cause in the case.

The trafficker’s bond was denied, as the judge was afraid the trafficker would retaliate against those who exposed her. This arrest was not the first time the trafficker has been in trouble, as a juvenile she was charged with disorderly conduct and assault. Before the arrest, the trafficker was already facing charges for driving on a suspended license and property theft. The trafficker was charged with three counts of child sex trafficking and one count of obstruction. The trafficker pled guilty to child sex trafficking conspiracy on January 2, 2013, and was sentenced to 216 months in federal prison. This case was brought as part of an FBI investigation in conjunction with the local Police Department and part of Project Safe Childhood (PSC).

Figure 12. Case study 2 – Map of victim movement by sex trafficker.

Group Trafficking Operations

Group Makeup

The 1,416 sex traffickers in this study made up 763 separate cases when they were grouped together with their codefendants. Each group had an average of 1.98 sex traffickers (SD = 2.378), with a minimum number of one trafficker per group and a maximum of 38 sex traffickers found in a group. These cases had an average of 2.25 adult and minor victims (SD = 3.462), with a minimum of zero victims (police sting cases) and a maximum of 60 victims in one case. When this is restricted to minor victims only, the average number of underage victims is 1.75 (SD = 1.627), with a minimum of zero victims (police sting cases) and a maximum of 16 underage victims in one case. Nearly one-third of these cases included both minor and adult victims (N = 242, 31.7%), meaning that two-thirds included only underage victims. Furthermore, almost three-quarters of the cases had more underage victims than adult victims (N = 545, 71.4%) showing a preference for minors as victims.

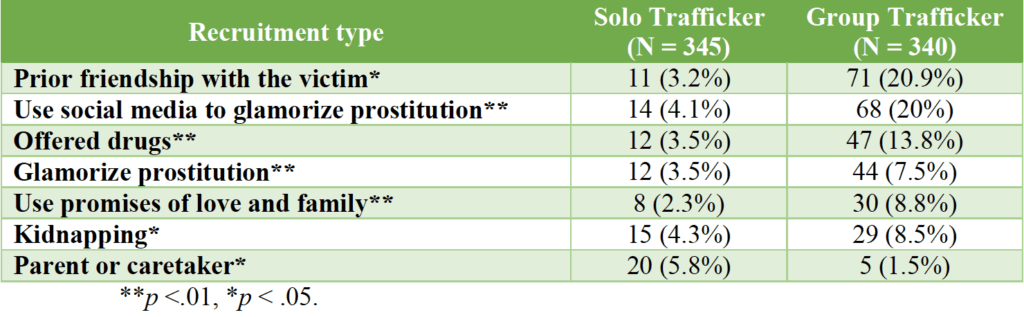

Group Recruitment Tactics

Sex traffickers used many different tactics to find and recruit their victims. In almost a quarter of the cases (N = 177, 23.2%), the sex traffickers had victims who were runaways. They used promises of money and wealth (N = 81, 10.6%), offered victims a place to stay in many cases (N = 78, 10.2%), also used friendship (N = 80, 10.5%) or romantic relationships (N = 77, 10.1%) to recruit their victims.

Table 14. Group sex trafficker recruitment methods, by type.

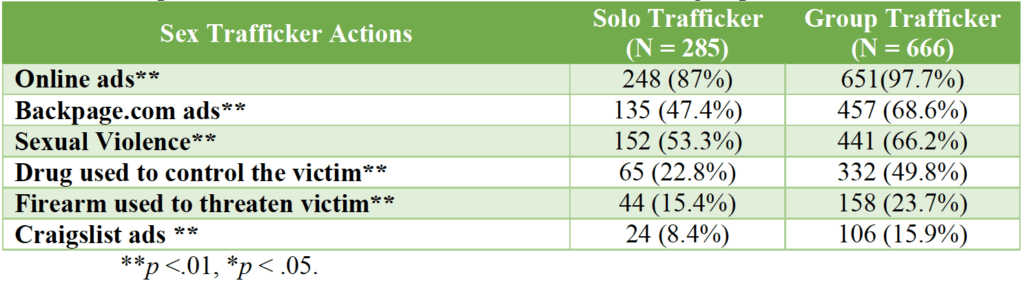

Group and Solo Sex Traffickers

The majority of the sex traffickers worked in groups of at least two people (n =959, 67.8%) compared to solo sex traffickers (n = 455, 32.2%). Solo sex traffickers chose slightly younger victims (M = 15.25 years old) than group sex traffickers (M = 15.4 years old). The female sex traffickers were significantly more likely to be in a group (n =285, 82.6% of females) than males (n = 672, 63%) (χ2 (2, N = 1,412) = 47.81, p = .001).

Victim Characteristics

Group sex traffickers were more likely to recruit a victim that was addicted to drugs (χ2 (1, N = 677) = 18.76, p = .001), a runaway (χ2 (1, N = 720) = 7.98, p = .003), was homeless (χ2 (1, N = 682) = 20.8, p = .001), and were more likely to have a history of sex trafficking (χ2 (1, N = 674) = 3.41, p = .05) than solo sex traffickers.

Recruitment and Tools

Recruiting by group sex traffickers was more likely to be based on a previous friendship with the victim (χ2 (1, N = 685) = 3.6, p = .037), glamorizing prostitution (χ2 (1, N = 687) = 24.51, p = .001), and promises of money and wealth (χ2 (1, N = 677) = 18.76, p = .001). Group sex traffickers were more likely to have bought tickets to travel for their victims (χ2 (1, N = 691) = 5.2, p = .02) and were more likely to have offered their minor victim a place to stay (χ2 (1, N = 689) = 24.76, p = .001).

Table 15. Comparison of sex trafficker use of violence, solo trafficker vs. group of sex traffickers.

Solo sex traffickers were significantly more likely to be a parent or caretaker of the victim (χ2 (1, N = 682) = 9.16, p = .002). Solo sex traffickers were more likely to have a criminal history including prior crimes against children (χ2 (1, N = 689) = 24.76, p = .001). Technology as a means to sell the victim was significantly more likely to be used by the group sex traffickers (n = 666, 69.4%) than the solo sex traffickers (n = 284, 62.4%).

Table 16. Comparison of sex trafficker actions, solo trafficker vs. group of sex traffickers.

Table 17. Comparison of sex trafficker characteristics, solo trafficker vs. group of sex traffickers.

Arrest Information

Arrest Methods

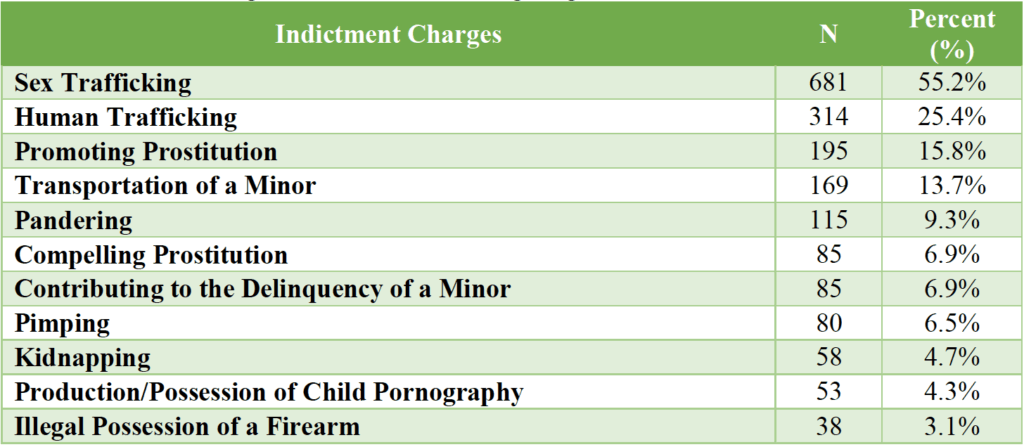

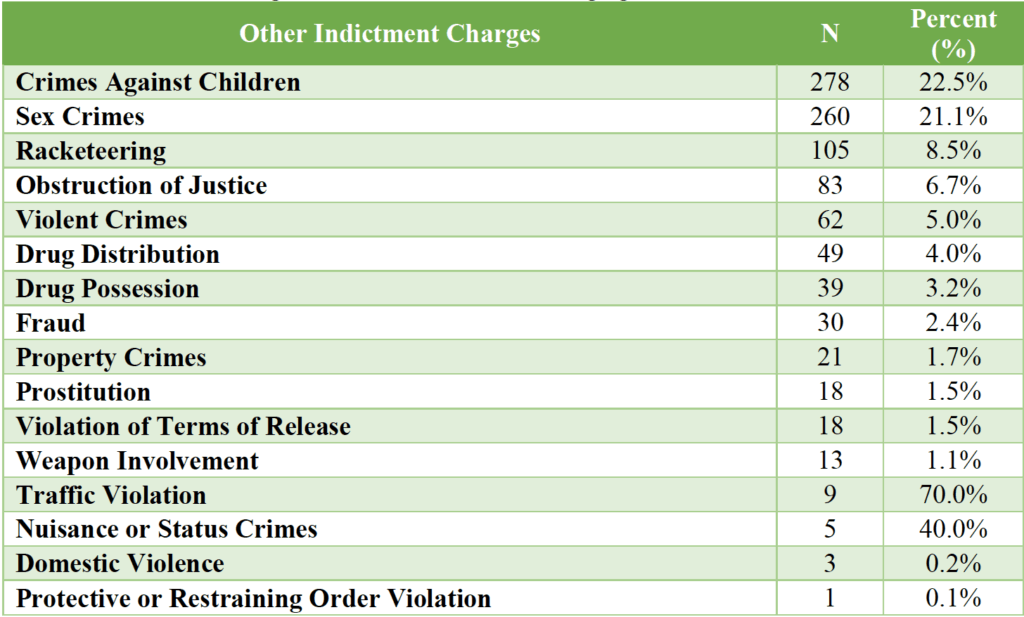

Law enforcement officers were able to use a variety of strategies to identify trafficking situations and arrest sex traffickers. Most often, police identified a trafficking situation reactively, when it was reported to them (N = 296, 38.8%). In this case, a victim was the most likely person to report to the police (N = 137, 18.0%), followed by a victim’s family member (N = 80, 10.5%), and any anonymous callers, authority figures, or agencies. Other times, victims were arrested in stings conducted by undercover police officers posing as buyers (N = 159, 20.8%). In a large number of cases (N = 126, 16.5%), police were aware that the person they were meeting to engage in prostitution with was a minor, usually because they had found photos of the underage victim in an online ad (N = 74, 9.7%) and recognized them as a minor. In a number of cases, police were able to recognize the trafficking situation based on warning signs (N = 60, 7.9%), which usually happened during traffic stops (N = 32, 4.2%). were second most common (n = 314, 25.4%). Charges relating to crimes against children (n = 278, 22.5%) and sex crimes (n = 260, 21.1%) were also common. Other common charges include charges related to promoting prostitution (n = 195, 15.8%) and transportation of a minor (n = 169, 13.7%).

Table 19. Sex trafficking related indictment charges against the sex traffickers.

Table 20. Indictment charges unrelated to sex trafficking against the sex traffickers.

Pleas and Trials

Sex traffickers’ pleas to their indictment charges was available in 856 cases 60.5%. A majority of the sex traffickers pled guilty or agreed to a plea bargain with the court (N = 606, 70.8%). Only one-quarter pled not guilty (N = 216, 25.2%), and a very small number of defendants pled no contest, or nolo contendere (N = 34, 4.0%). Less than one-quarter of these cases went to trial (N = 207, 24.4%).

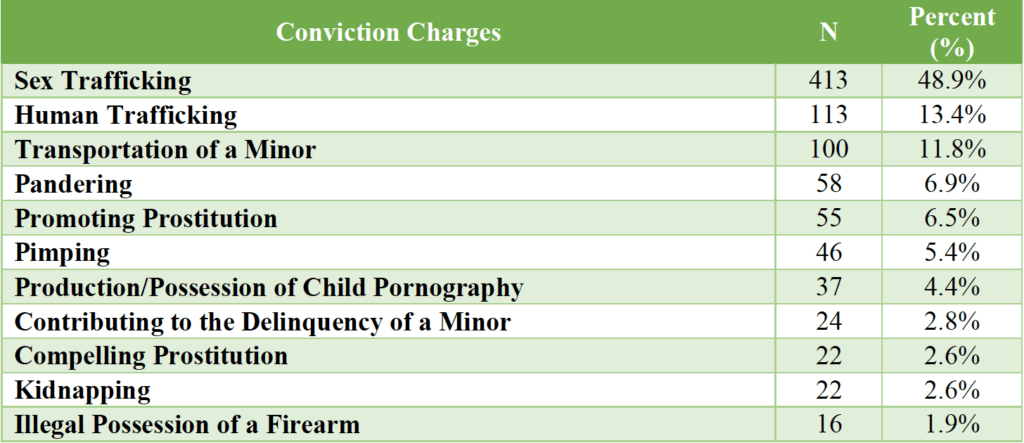

Conviction

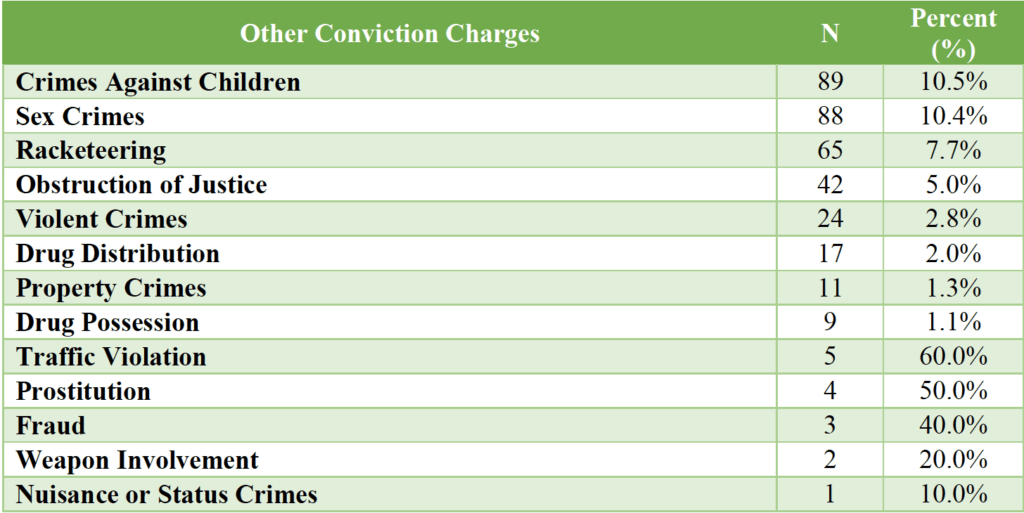

Conviction information was available for 845 cases (59.7%). For those who were convicted, they were convicted of an average of 2.13 criminal charges, with the largest number at 48 charges. These crimes tended to be mid-level felonies, slightly lower than the indictment charges. As with indictment charges, sex traffickers were most commonly convicted of charges related to sex trafficking (N = 413, 48.9%), followed by human trafficking (N = 113, 13.4%). Crimes against children (N = 89, 10.5%) and sex crimes (N = 88, 10.4%) were also common. Other common crimes included those related to transportation of a minor and pandering, respectively. Charges were dropped completely in 42 cases, or 5.0%.

Table 21. Sex trafficking related conviction charges against the sex traffickers.

Table 22. Conviction charges unrelated to sex trafficking against the sex traffickers.

Sentencing

Sentencing information was available for 751 (53%) of the sex traffickers. A large majority of the sex traffickers with known sentences were sentenced to jail or prison time (N = 681, 90.7%). Out of those sex traffickers, 30 were sentenced to life in prison (4.4%) and 13 were sentenced to a maximum of life in prison (1.9%), with an average minimum of 579.38 months (appx. 48 years in prison). For those sentenced to a time of less than life in prison, the average sentence was 162.79 months or approximately 13.5 years in prison. A total of 27 sex traffickers (4.0%) received a sentence of “time served,” in which the time they had already served in jail during their trial was deemed a sufficient sentence. One sex trafficker was deported. Figure 13. Maximum incarcerations sentences of sex traffickers, by month.

Figure 13. Maximum incarcerations sentences of sex traffickers, by month.

After serving a jail or prison sentence, 267 sex traffickers were sentenced to serve time on parole or placed on supervised release (39.2%). Of those sentenced to parole, 20 sex traffickers were sentenced to serve life on parole or supervised release (7.5%). Only one trafficker (0.4%) was sentenced to serve a maximum of life on parole or supervised release, with his minimum sentence set at 60 months.

For the sex traffickers who were not sentenced to serve life on parole or a maximum of life on parole, their average sentence was 88.73 months, or approximately 7 years. Sex traffickers who were not sentenced to jail or prison time were often sentenced to serve probation time (N = 37, 4.9%). Those who were sentenced to probation received an average sentence time of 53.62 months, or about 4.5 years.

Information on restitution payment to victims was found for only 65 sex traffickers (4.6%). Those sex traffickers were required to pay an average of $70,045.94 to their victims, with a minimum restitution amount of $100 and a maximum restitution amount of $538,250. Furthermore, very little information was found on sex offender registration. According to case reports, only 157 sex traffickers were required to register as sex offenders (11.1%).

Trends over the Six Years

These maps show an increase in sex trafficker arrests of minors throughout the United States over the six-year study period. In 2010, arrests totaled only 97, but totals steadily increase with each passing year. Total arrests in 2015 were 360, almost four times many as many in 2010. The amount of states in which arrests are taking place jumps each year and one can visualize this progression with the gradual filling of shaded states. The 2010 and 2011 maps look sparse when compared to the 2015 map. This is showing that awareness of sex trafficking is spreading across state lines and into communities where it had not been noticed previously.

The rate of sex trafficker arrests per 1 million persons also shows an increase over the six years. The rates for 2010 and 2011 represent only one state having a rate higher than 1 sex trafficking arrest per 1 million persons. As the maps progress, 2012 shows 8 states with a rate higher than 1 and 2013 reveals 14 states with a rate higher than 1. 2014 shows 10 states and 2015 shows 16 states plus the Virgin Island with a rate higher than 1. 2014 and 2015 also show high spikes in rates with Rhode Island and the Virgin Islands having rates up to 10 per 1 million persons compared to the relative high of three per 1 million for other years. The increased arrest rates reveal improved police awareness and vigilant proactive police work throughout the United States.

Figure 14. The rate of sex trafficker arrests from 2010 to 2015.

Individual Sex Traffickers Across the Six Year Study

Demographics

The gender makeup of this sample was compared using chi-square analysis across all years. The third gender option, “Other”, was excluded from the analysis since there was only one trafficker whose gender was not “Male” or “Female” in all six years. With this option excluded, analysis showed significant differences as time passed (χ2 (5, N = 1413) = 13.651, p < .05). The percentage of female sex traffickers increased from 13.4% 2010 to 24.2% 2015, hitting a peak in 2012 when 27.2% of the sample was female.

Analysis also revealed that there were significant differences in the average age of sex traffickers as the years passed [F (5,1361) = 3.173, p = 0.007]. In 2010, sex traffickers’ average age was 29.55 years, but this age decreased to 27.46 years in 2015, showing that sex traffickers tended to be younger on average as time passed.

Gang Affiliation, and Criminal History

Gang affiliation was measured and compared across all years. This variable measured whether or not a trafficker was a known gang member or otherwise associated with a gang or organized crime group. Analysis revealed that there were significant differences in the amount of sex traffickers affiliated with gangs as the years passed (χ2 (5, N = 1208) = 152.444, p < .001). Almost half of the sample, 48.5%, was affiliated with a gang in 2010. In 2015, the amount of sex traffickers who were associated with a gang decreased to 6.9% of the sample. The presence of a criminal history and different types of crimes were measured when they were available to researchers, and compared across all years. The number of sex traffickers with a criminal history of violent crimes, such as assault, battery, robbery, and other crimes against people, increased as the years passed (χ2 (5, N = 267) = 18.485, p < .01). In 2010, 5.2% of sex traffickers had a criminal history involving violent crimes, but in 2015, this figure increased to 8.3%, reaching a peak of 9.8% in 2014.

Involvement in Trafficking

Researchers measured each trafficker’s involvement in their respective trafficking operations by noting the specific actions they committed to further the operations. These actions were divided into the following categories:

a. Recruiting victims

b. Taking sexually inappropriate photos of the victims

c. Posting prostitution advertisements for the victims

d. Providing shelter for or living with victims

e. Renting hotel rooms for shelter or prostitution acts

f. Providing transportation or money for transportation to the victims g. Giving victims drugs and/or alcohol

h. Teaching victims how to engage in prostitution

i. Providing security for victims during prostitution activities

j. Arranging appointments with johns/buyers k. Supervising victims during prostitution activities

l. Collecting money made from prostitution acts with victims

m. Physically assaulting victims

n. Sexually assaulting adult victims or engaging in sexual acts with underage victims

o. Threatening victims

p. Dictating prices for prostitution acts

q. Setting an earning quota for victims

Analysis revealed changes in prevalence for several of these actions. The amount of sex traffickers who engaged in recruitment increased as the years passed (χ2 (5, N = 1219) = 12.332, p < .05). In 2010, the amount of sex traffickers who engaged in recruitment was at 38.1%. This figure increased to 52.2% in 2013, and then dropped back to 36.7% in 2015. The proportion of sex traffickers who posted ads followed a similar trend to those who recruited victims (χ2 (5, N = 1221) = 11.726, p < .05). In 2010, 37.1% of sex traffickers posted ads, which increased to 46.7% in 2013 and decreased again to 36.9% in 2015. An opposite trend was revealed for sex traffickers who provided shelter for victims (χ2 (5, N = 1217) = 41.829, p < .001). The proportion of trafficker who provided shelter was at 12.4% in 2010. This dropped to 8.2% in 2014 and then increased to 16.9% in 2015, creating a general upward trend. The amount of sex traffickers who rented hotel rooms increased significantly over the years (χ2 (5, N = 1227) = 96.892, p < .001) from 21.6% in 2010 to 37.2% in 2015. The sex traffickers who provided transportation for victims increased slightly as the years passed (χ2 (5, N = 1236) = 37.161, p < .001) from 41.2% in 2010 to 45.8% in 2015.

The amount of sex traffickers who provided drugs and alcohol to their victims increased between 2010 and 2015 (χ2 (5, N = 1221) = 26.706, p < .001). The percent of sex traffickers giving their victims drugs and alcohol increased from 14.4% in 2010 to 19.4% in 2015, shortly after hitting a low mark of 11.1% in 2013. The amount of sex traffickers who took charge of arranging appointments with buyers also increased significantly over the years (χ2 (5, N = 1219) = 81.712, p < .001). This increased from 6.2% in 2010 to 22.8% in 2015. Sex traffickers who supervised the victims also increased slightly (χ2 (5, N = 1216) = 59.610, p < .001) from 5.2% in 2010 to 10.3% in 2015, shortly after dropping to 0.7% in 2013. The amount of sex traffickers who collected money from victims made an interesting trend over the years (χ2 (5, N = 1236) = 16.133, p < .01). It increased from 58.8% in 2010 to 84.3% in 2011, and then decreased again to 71.5% in 2012, where it stayed until 2015, when it decreased again to 50.8%.

Trafficking Operations

Group Makeup

The type and size of the sex traffickers’ operations were measured by whether or not the sex traffickers had adult victims as well as minor victims, and by counting the number of known minor victims that were involved. The prevalence of trafficking operations with adult and minor victims decreased significantly over the years (χ2 (5, N = 659) = 18.020, p < .01), meaning that more sex traffickers victimized minors exclusively in later years. In 2010, 39.5% of the cases included underage victims and adult victims. This decreased significantly to 25.7% of cases in 2015 that included underage and adult victims. This means that almost three-quarters of the trafficking groups in 2015 had minor victims only. Furthermore, as expected, the prevalence of trafficking operations with more minor victims than adult victims increased significantly (5, N = 710) = 11.741, p < .05). Almost two-thirds of cases, 63.2%, had more minor victims than adult victims in 2010, which increased to 80.7% in 2014 and dropped suddenly to 63.8% in 2015.

There were also changes in the average number of sex traffickers involved in each operation as time went on [F (5,757) = 3.244, p = 0.007]. In 2010, there were an average of 2.87 sex traffickers involved in a group and prosecuted together. This average amount decreased 35 significantly to only 1.80 sex traffickers per group in 2015. This shows that sex traffickers were more likely to engage in sex trafficking on their own in later years, rather than with a partner or in a group.

There were also changes in the average number of underage victims that were involved in each operation as time passed [F (5,694) = 2.411, p = 0.035]. The average number of minor victims increased from 1.74 in 2010 to 2.54 in 2011, which then decreased again to 1.54 in 2013 and 1.72 in 2015.

Recruitment Tactics

Recruitment tactics were measured by researchers using victim vulnerabilities and the different tactics sex traffickers used to gain the trust of their victims. The only item that showed significant change in prevalence over the years was the victim vulnerability of being a runaway (χ2 (5, N = 639) = 60.525, p < .001). The amount of cases in which at least one victim was a runaway decreased from more than one-third in 2010 (34.2%) to 16.7% in 2013 and increased again to 27.1% in 2015.

Trafficking Tactics

Other trafficking tactics were measured by the types of locations that were used as places for victims to engage in prostitution acts with buyers. These location types include: a trafficker’s or associate’s apartment, a trafficker’s or associate’s house, a hotel room, on the street, at a nightclub or strip club, and at outcall locations such as buyer’s homes. There were significant changes in the prevalence of three of these trafficking locations as the years passed. The use of a trafficker’s or associate’s house decreased significantly (χ2 (5, N = 418) = 18.988, p < .01). In 2010, 10.5% of cases included trafficking from a house and in 2011, 27.8% of cases included trafficking from a house. This figure steadily decreased over the years until 2015, when only 6.2% of cases included trafficking from a house. The prevalence of trafficking operations in which victims walked the streets in areas known for prostitution also decreased significantly (χ2 (5, N = 408) = 17.223, p < .01). The figure spiked from 7.9% in 2010 to 33.3% in 2011, which then decreased again to 10.5% in 2015. Finally, the prevalence of cases in which victims were taken to outcall locations decreased significantly as the years passed (χ2 (5, N = 432) = 16.616, p < .01). In 2010, 28.9% of cases included trafficking to outcall locations, and in 2015, only 12.9% of cases included this.

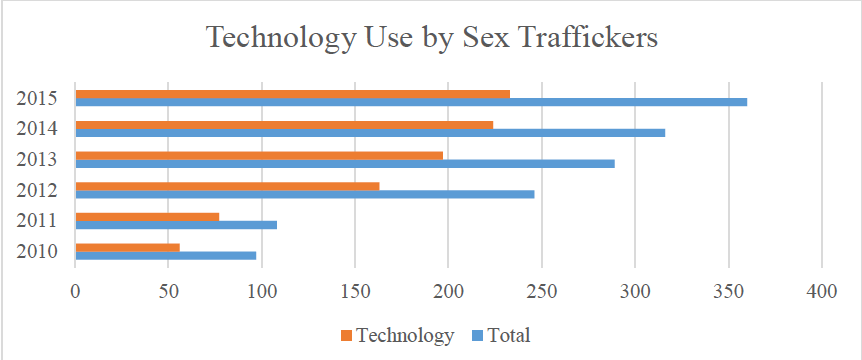

The use of technology in the sex trafficking situations increased over the five years from 56 cases in 2010 to 233 in 2015.

Figure 15. Use of technology by sex traffickers over time.

Backpage.com was involved in 14.4% of the cases in 2010 and 38.3% of the cases in 2015.

Figure 16. Use of Backpage.com in sex trafficking exploitation.

Analysis revealed that drug involvement and use in these trafficking cases changed significantly as time passed. Drug involvement was noted by researchers when drugs were used as a control method, or simply when drugs were present in the case and the sex traffickers were charged with possession or distribution. Drug involvement decreased overall (χ2 (5, N = 605) = 77.547, p < .001) from 34.2% in 2010 to 26.7% in 2015 after increasing in 2011 to 47.2%. Drug control was specifically noted by researchers when sex traffickers provided drugs and alcohol to underage victims and/or used controlled substances to keep victims compliant. Drug control also decreased overall (χ2 (5, N = 587) = 68.597, p < .001) from 26.3% in 2010 to 18.6% in 2015 after increasing in 2011 to 36.1%.

Information on the use of different types of violence as control tactics was gathered and measured by researchers. Physical violence included any hitting, kicking, beating with weapons, or other infliction of physical harm. Sexual violence included any non-consensual sexual activity, which includes rape and sexual assault against adult and minor victims, as well as any sexual activity with minor victims, since they cannot consent. Psychological violence includes threats against victims, their families, and other forms of verbal and psychological abuse. The prevalence of all three of these types of violence decreased significantly as the years passed. The use of physical violence decreased as the years passed (χ2 (5, N = 586) = 55.599, p < .001). Almost half of the cases in 2010 involved the use of physical violence against victims (44.7%), which decreased to less than one-quarter in 2015 (21.4%). The use of sexual violence also followed a similar trend (χ2 (5, N = 587) = 52.432, p < .001). In 2010, 44.7% of cases involved the use of sexual violence against victims, and this decreased to only 23.3% of cases in 2015. Finally, the use of psychological violence also decreased (χ2 (5, N = 596) = 56.616, p < .001). In 2010, 47.4% of cases involved the use of psychological violence, and in 2015, only 24.8% of cases did.

Criminal Justice System

Arrest methods were analyzed to determine how law enforcement officers became aware of the trafficking situation, as well as the subsequent steps they took to investigate, rescue the victims, and arrest the sex traffickers. The rate of victims contacting police for help decreased significantly over the years (χ2 (5, N = 670) = 11.830, p < .05). In 2010, 31.6% of cases were discovered when victims contacted law enforcement. This decreased to 17.1% in 2015. The use of police stings in cases where law enforcement officers knew that there was an underage victim involved fluctuated slightly over the years (χ2 (5, N = 685) = 13.866, p < .05). It dipped from 21.1% in 2010 to 11.7% in 2012, and then back up to 17.6% in 2015. However, the use of a long-term investigation became much more common as time passed (χ2 (5, N =673) = 63.012, p < .001). It increased from 15.8% in 2010 and 5.6% in 2011 to 24.8% in 2015.

The FBI was involved in helping to investigate and prosecute a large number of these cases (N = 318, 41.7%). The FBI was involved in the investigation of these cases less and less commonly as time passed. FBI involvement decreased significantly over the years (χ2 (5, N = 659) = 40.940, p < .001). The FBI was involved in more than half of the trafficking cases in 2010 (65.8%), which decreased to only 27.6% in 2015.

Indictment

Researchers gathered information on the level of the prosecuting court in each of these cases. It was noted whether cases were originally prosecuted in a local or county court, a state court, or a federal court. As time passed, trafficking cases were much more likely to be prosecuted in local or state courts than in federal courts (χ2 (5, N = 1299) = 68.916, p < .001). In 2010, a large majority of these cases were brought to federal court (86.6%) rather than a state court (6.2%) or a local court (7.2%). The amount of cases brought to federal court decreased significantly so that in 2015, only 41.7% of these sex trafficking cases were immediately sent to federal court, 17.2% were at a state court, and 26.9% were at a local court.

Researchers gathered information on the types of crimes sex traffickers were charged with in their indictments, using the most recent indictment, which often meant using a superseding or secondary superseding indictment. Charges that were often used in these trafficking cases, such as charges against crimes related to child pornography, prostitution, kidnapping, and human and sex trafficking, were closely analyzed. There were significant changes in the use of different types of common indictment charges as the years passed.

The amount of sex traffickers who were charged with contributing to the delinquency of a minor, related, or similar charges increased as time passed (χ2 (5, N = 1235) = 17.461, p < .01). Only 1.0% of sex traffickers were charged with this crime in 2010, which increased to 8.9% in 2012 and 5.8% in 2015. The amount of sex traffickers who were charged with promoting prostitution and related crimes such as benefitting from prostitution also increased over the years (χ2 (5, N = 1235) = 24.429, p < .001). The use of this charge increased from 3.1% in 2010 to 17.1% in 2014 and 16.1% in 2015. The use of pandering charges increased (χ2 (5, N = 1235) = 14.008, p < .05) from 4.1% in 2010 to 12.2% in 2012 and 6.7% in 2015. The use of charges related to compelling prostitution decreased (χ2 (5, N = 1235) = 12.438, p < .05) from 6.2% in 2010 and 10.2% in 2011 to only 3.6% in 2015.

Human trafficking charges became more common (χ2 (5, N = 1235) = 39.402, p < .001). In 2010 only 13.4% of sex traffickers were indicted with charges related to human trafficking, which increased to 26.9% in 2015. However, the use of charges specifically related to sex trafficking decreased significantly (χ2 (5, N = 1235) = 40.368, p < .001). In 2010, 73.2% of sex traffickers were indicted with charges related to sex trafficking and in 2015, only 38.3% of sex traffickers received sex trafficking charges.

Pleas and Trials

After sex traffickers were indicted, many had a choice to take a plea deal with the court or to plead not guilty to the charges. Those who pleaded not guilty could participate in a trial with a jury of their peers. The proportion of sex traffickers whose cases went to a jury trial decreased significantly as time passed (χ2 (5, N = 850) = 12.084, p < .05). More than one-third of cases went to trial in 2010 (34.0%), which decreased to only 8.9% of cases going to trial in 2015.

Conviction

The average number of criminal charges that sex traffickers were convicted with increased significantly as time passed [F (5,840) = 3.115, p = 0.009]. In 2010, sex traffickers were convicted with an average number of 1.46 criminal charges. This increased to 2.86 criminal charges in 2015. Given the significant decrease in the amount of cases that went to trial, researchers would have expected the average number of conviction charges to also decrease, since plea agreements tend to result in less severe convictions, and cases that go to trial result in more severe convictions with a higher number of conviction charges.

Sex traffickers were convicted of the crimes that they pleaded guilty to or that they were found guilty of in a trial. Conviction charges were closely analyzed by researchers in the same way indictment charges were analyzed. Only two types of conviction charges showed significant changes as the years passed. Conviction in human trafficking charges increased (χ2 (5, N = 805) = 15.345, p < .01) from 4.1% in 2010 to 11.1% in 2011 and 6.4% in 2015. However, conviction in sex trafficking charges decreased significantly (χ2 (5, N = 805) = 18.403, p < .01). In 2010, 40.2% of sex traffickers were convicted with charges related to sex trafficking, and in 2015, only 14.7% of sex traffickers were convicted with charges related to sex trafficking. Sentencing The average parole sentence, or sentence for supervised release after serving jail or prison time, increased significantly as the years passed [F (5,240) = 3.439, p = 0.005]. The average parole sentence in 2010 was 81.58 months or nearly 7 years. This increased significantly to 103.57 months in 2015, or about eight and a half years.

DISCUSSION

This study found 1,416 persons in the U.S. who were arrested for the sex trafficking of a minor. The number of arrests for the sex trafficking of a minor increased steadily over the six years of this study. Establishing the number of arrests for sex trafficking a minor in the U.S. is helpful for a number of reasons: this number helps to develop parameters for the scope of the problem of sex trafficking of children in the U.S. and establishes that the sex trafficking of minors is a real and present issue that should be discussed at local, state and federal levels, and lastly promotes the discussion and implementation of strategies regarding prevention, identification, and intervention. In 2015 alone, there were 360 persons arrested for sex traffickers of minors. This is an indicator of the vast amount of work for law enforcement regarding collecting information and evidence to build each case to charge the offender with sex trafficking of a minor. The impact on the courts of these cases is also important to consider with 360 cases of this type being presented in one year alone. This steady increase of cases indicates the probability that there will be an increase in cases in 2016 and into the future. This increase can in part be credited to a widespread sex trafficking-focused training initiative around the U.S. by federal agencies including the Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Local and state level trainings have convened throughout the U.S. with a specific focus on training social service and mental health providers, community corrections, law enforcement, and prosecutors. Professions that work with children in other settings, such as medical personnel and educators, may also benefit from training.

Four states, Alaska, Hawaii, West Virginia, and Wyoming, did not have any arrests of persons charged with sex trafficking of minors from 2010 to 2015, which may indicate a number of issues. Perhaps sex traffickers of minors are being identified and arrested but are being charged with other types of criminal charges, or sex traffickers of minors are not being identified or charged. Future research should explore these states, including the extent of sex trafficking trainings available to their law enforcement and prosecutors, as well as their city and state policies to determine if there are any statutory barriers to arresting sex traffickers of minors.

A third of the 1,416 sex trafficking of minor cases involved the transportation of a minor across state lines, indicating that multiple jurisdictions may be involved in each case. This partially explains why 54% of the cases were at the federal level. This finding emphasizes the need to involve and provide training to state and county police and transportation industry workers, including those related to buses, trains, airplanes and rental cars. In addition, trainings focused on persons working along transportation corridors, such as the focus of Truckers Against Trafficking, to train truck drivers and those working in gas stations and convenience stores along highways.

The majority of the individuals arrested for sex trafficking of a minor were males, although female arrests increased over the duration of the study. The role of female sex traffickers was most likely as part of a group, and more than half of the women fit into the role and were identified as a ‘bottom.’ This role includes being a prostituted person, which was 40 confirmed by some having prior arrests for prostitution, as well as being a trusted confidant to the male sex trafficker. This role also includes recruiting other victims, teaching the rules of prostitution, and in some cases participating in the punishment and abuse of the victims. The cases involving female sex traffickers targeted the most vulnerable victims: those who were homeless, runaway, or drug addicted. Female sex traffickers were also more likely to be involved in cases when a caregiver or guardian was the sex trafficker.