BY THE DEMOCRACY & HUMAN RIGHTS WORKING GROUP

* The Democracy & Human Rights Working Group is a nonpartisan initiative bringing together academic and think tank experts and practitioners from NGOs and previous Democratic and Republican administrations, seeking to elevate the importance of democracy and human rights issues in U.S. foreign policy.

It is convened by Arizona State University’s McCain Institute for International Leadership. The views expressed here do not necessarily represent the positions of individual members of the group or of their organizations.

For decades, the United States has supported democracy and human rights around the world for the following reasons:

- The United States was founded on the principles of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, and Americans believe that all people should enjoy these rights.

- The United States is safer and more prosperous in a more democratic world and should take the lead in advancing this cause.

- Free nations are more economically successful, stable, reliable partners, and democratic societies are less likely to produce terrorists, proliferate weapons of mass destruction, or engage in aggression and war. This means that the advance of democracy benefits not just the U.S., but order and peace around the globe.

- Major problems we face in the world come from authoritarian regimes (and non-state actors) that seek to blunt the advance of democracy and see it as a threat to their own hold on/grab for power.

- Democracy advocates and human rights defenders look to the U.S. for moral, financial, and political leadership and support, making American leadership indispensable. Remaining silent or reducing the profile of these issues abandons people who, in many cases, sacrifice their liberty and lives struggling for a more democratic society.

- How a regime treats its own people is often indicative of how it will behave in foreign policy, thus getting a government to respect universal values and promote democratic development advances the cause of freedom.

- Given the option, most people around the world would choose to live in free societies. According to the most recent World Values Survey, more than 82% of respondents believe having a democratic system of government is a good thing.

The environment for democracy and human rights – both as ideas and for the people and groups on the front lines struggling toward them – has become more challenging due to turmoil in the MENA region as well as economic crises that have left many democracies inward focused. Young people feel disenfranchised and lack economic opportunities. Citizens of many countries feel they suffer from a lack of dignity, justice and respect. As a result, anti-democratic forces are far more empowered and emboldened today than at any time since the Cold War. The resurgence of Russia, Iran, China, the spread of ISIS, and the aftermath of movements in the Arab world have created multiple global challenges to the efforts of democracy and human rights activists. Likewise, the current instant information age – which has provided new means of helping these activists – has also allowed the anti-democrats to flourish. This is a contested space; therefore, it is important to make clear that the United States stands firmly with those seeking to build democratic societies that allow people to live in freedom, lead to greater economic success, better protect intellectual property rights, and provide a more stable investment environment.

Given the option, most people around the world would choose to live in free societies.

In the current, complex environment, there is a need for a renewed, more modern effort to support democracy. We need to elevate democracy promotion and human rights to a prominent place on the American foreign policy agenda by supporting indigenous forces and helping create space for them to work within their own country.

We should seek to promote universal values – freedoms of expression, assembly, association, and religion – without trying to impose the American model on other countries or through the barrel of a gun. We need to partner with other democracies, both those with a history of freedom and those who have more recently transitioned, to strengthen efforts to spread these universal values. This involves supporting:

- Rule of law and accountability, Separation of powers, an independent judiciary, and checks-and-balances,

- Free, fair, and competitive elections and political party development,

- Respect for women’s rights,

- A diverse and independent media, including internet freedom,

- A vibrant civil society,

- Democratic governance and representative, functional institutions,

- Respect and tolerance for minority groups and for religious freedom, and Protection of property rights.

Promoting these universal values involves training, building capacity, helping to establish systems of democratic governance, and fostering dialogue, both in countries that are struggling to establish democracy and those that are led by opponents of democracy. Countries that adopt and follow these basic elements of democratic development are better allies of the United States and better citizens of the world. Authoritarian regimes, by contrast, by their very nature pose a challenge to our way of life and to our security, as well as to the security of others.

Supporting democratic forces, however, is only part of the equation, albeit a large part. We also should push back against the authoritarian challenge by imposing consequences on those involved in serious human rights abuses. Unless authoritarian leaders incur costs for their antidemocratic actions, they will see no reason to change their behavior.

The United States government has many tools at its disposal both to assist those who are struggling for freedom and to pressure anti-democratic forces to change their behavior. These tools exist across many areas of U.S. foreign policy, from diplomatic tools and military assistance to trade agreements and economic partnerships.

As much as possible, these tools should be leveraged in a coordinated manner with like-minded democracies to support those fighting for democratic change in countries around the world.

MAKING ARGUMENTS IN SUPPORT OF ADVANCING FREEDOM

BY THE DEMOCRACY & HUMAN RIGHTS WORKING GROUP

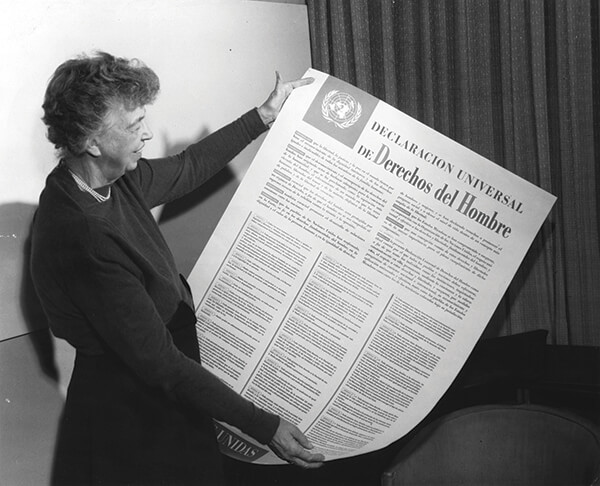

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948, defined the terms “fundamental freedoms” and “human rights.” These include rights and freedoms of association, religion, speech, and assembly – many of which are still lacking or limited in many other countries.

While the United States has played the role of global champion of these rights over the last several decades, an aversion to promoting democracy and human rights is shared by some on both the left and right of the political spectrum. These “doubters” set up false choices in which policymakers would be pressured to choose promoting either our values or our interests. In fact, promoting our (or universally recognized) values advances U.S. interests, for the two really are inseparable. Further, the skeptics suffer from a fundamental misunderstanding about democracy and human rights promotion. In the short term, in a few cases, there may be a need to temporarily emphasize other interests, but in the medium and longer term, democracy and human rights concerns cannot be neglected if we want sustainable relations with other countries and are to preserve our credibility in the world. Following are some of the most widely heard arguments against promoting democracy and human rights:

THE “ARROGANCE” ARGUMENT

Point: It is not America’s role or responsibility, “doubters” argue, to tell other countries what kind of political system is in their interest, to impose our system on others, or to criticize other governments for human rights abuses, especially when we ourselves are not perfect.

Counterpoint: It is our business – and in our interest – to promote freedom around the world; indeed, the United States has a special obligation to help those fighting to live in freedom and those with a limited voice in their society often look to us to play that role. We do not insist that others follow the American model, and recognize that we also make mistakes, but we should urge governments to respect universal human rights and democratic principles, even while developing their own character, consistent with international covenants and agreements that they have signed. Rather than attempting to dictate the directions countries take, we are instead refusing to remain silent when peaceful political activity is crushed or made illegal.

THE “DOMESTIC PRIORITIES” ARGUMENT

Point: We should focus on problems at home before going around the world lecturing others.

Counterpoint: The world will not wait for the United States to “get our own house in order.” In fact, voids in leadership would likely be filled by governments or movements that not only do not share our interests, but fight actively against them. We have to be able to do both: address our own shortcomings while supporting democracy movements and showing solidarity with human rights activists elsewhere. That is the best way to serve U.S. national interests, and activists and freedom advocates around the world look to us for support and leadership. Isolationism will not result in a more stable, safe, or economically robust world.

THE “ELECTIONS ARE DANGEROUS” ARGUMENT

Point: We have pushed elections prematurely in places, with very undesirable results; we’d be better both off with the known party in power than risk an unwelcome electoral change and the “devil” we don’t know.

Counterpoint: It is true that unfavorable election results are a risk. Every country has to experience its own path to democracy, and sometimes that involves less than ideal (from a U.S. point of view) changes in leadership. However, elections are not the be all and end all of democracy; much more is involved. The freedoms of the press and association are crucial components of having an informed electorate, for instance. In the long run, though, accountable governance is ultimately achievable only when citizens choose their own leaders through free elections. The election of anti-Western or anti-American leaders may make it harder for these countries to be embraced by the international community, but the hope is that those citizens will recognize the consequences of their votes and will then use the democratic process to make further changes that are ultimately better both for their own society and for our interests.

THE “WE CAN’T HAVE EVERYTHING” ARGUMENT

Point: If we promote democracy in a country, we harm our other interests with that country.

Counterpoint: Supporting democracy and human rights need not be mutually exclusive to pursuing economic and/or security interests. Indeed, we can enhance our overall interests by ensuring that democracy and human rights feature prominently in our relations with other countries. There is no denying that we maintain “double standards” with certain authoritarian allies; other authoritarian countries come to expect similar treatment. Further, such treatment has bolstered the arguments of those who believe the United States must choose one or the other interest. It is only when the United States consistently engages countries on both fronts that governments will realize they must deal with our leadership on a broad basis that includes democracy, human rights, economics and security. They will know they have no choice.

THE “ECONOMICS IS THE ANSWER” ARGUMENT

Point: We should focus on helping a country develop economically, and then with economic liberalization will come a middle class with a vested interest in democratic governance.

Counterpoint: Those who argue that the United States should focus on economic development first and then push for democratic development later risk aligning us with authoritarian regimes that delay loosening political controls as long as possible. The key is to urge progress on both the political and economic fronts and avoid either/or situations. We certainly have working relations with a number of governments that engage in gross human rights abuses and pursue an authoritarian track while realizing a rise in the standard of living, and those governments often continue to commit abuses. But our ability to have truly productive, sustainable partnerships with those regimes is inhibited by such abuses. Binary choices – either promoting democracy and human rights or advancing our economic and security interests – are best avoided if we want to influence these countries to improve their record in support for human rights and democracy. Perhaps more important, there is strong evidence that democracy actually has a positive effect on economic growth. According to a 2014 academic study of 184 countries from 1960 to 2010 (“Democracy Does Cause Growth” by Daron Acemoglu, Suresh Naidu, James A. Robinson, and Pascual Restrepo), a country that converts from a nondemocracy to a democracy experiences a 20% higher per capita GDP over the long term (30 years).

…the skeptics suffer from a fundamental misunderstanding about advancing democracy and human rights.

Overall, the world has experienced 6% higher GDP with the increased number of democracies over the last 50 years. Moreover, on balance, companies looking to invest or do business overseas prefer operating in environments where there is rule of law.

THE “IDEALISM VS. REALISM” ARGUMENT

Point: It is idealistic to think that we can change the way despots run their countries. The only way to engage dictators is in terms of self-interest – appealing to their economic or security needs to get what we want.

Counterpoint: That is a short-term view that over time has proved to be flawed, as free nations are more stable, prosperous and reliable partners. Repressive regimes are inherently unstable and rely on suppressing democratic movements and civil society to stay in power. As we witnessed in the Middle East in 2011, no one can predict when such regimes might collapse, but if we consistently encourage and support peaceful, democratic change, we will likely help reduce sudden upheavals and the risk of having the United States aligned with the “wrong” side when regime change eventually comes. While change rarely happens overnight, in the long-term the effort it takes to consistently impress upon autocrats the importance of democratic values and protecting human rights will eventually produce results. When change inevitably occurs, those who sought genuine democratic change will know the United States was on their side.

THE “DEMOCRACY PROMOTION IS REALLY REGIME CHANGE” ARGUMENT

Point: What democracy promotion really means is regime change through the use of force. The American people do not want to devote any more resources to toppling dictators – these countries need to deal with their own problems.

Counterpoint: The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were begun for reasons of national security, not to impose democracy. Once the regimes fell, the U.S. implemented its decades-old policy of supporting democratic activists internally to help them rebuild their governments; indeed, we had a responsibility to do so for the alternative was chaos (as we’ve seen in Libya). Regime change must be separated from the U.S. policy – implemented for the past 30 years through the National Endowment for Democracy and associated NGOs – of helping democratic activists establish the building blocks of democracy such as the rule of law, free elections, an effective civil society, and freedom of the press. We recognize that support for democracy can result in regime change by virtue of helping citizens find their political voice, even if that is not the primary purpose of such assistance.

THE “WE CAN’T MAKE A DIFFERENCE” ARGUMENT

Point: The United States has never been good at promoting democracy. Look at the state of the world today – chaos in the Middle East, Russian imperialism resurging, even some Latin American democracies struggling. Name one good example of U.S. democracy promotion efforts actually succeeding.

Counterpoint: In 1972, according to Freedom House, there were 44 countries rated as “free.” Today, there are 89 countries in that category. Clearly, the state of democracy in the world has improved. The establishment of democracy is not a short-term proposition. It takes time and commitment by those fighting for it, and the process is not necessarily a linear one. The United States has had democracy for nearly 250 years and we are still perfecting it, so we cannot expect other countries, especially those without democratic traditions or history, to get it right the first time. But ask the citizens of Mongolia, Tunisia, Poland, or Serbia whether the United States has helped them in their path toward democracy, and the answer is likely to be a resounding yes.

THE “NATIONS CAN SUCCEED WITHOUT DEMOCRACY OR HUMAN RIGHTS” ARGUMENT

Point: Democracy is not necessary for a country to be successful. Look at China or Singapore. They are huge (in the case of China), growing economies and have succeeded without democracy or human rights protections.

Counterpoint: China and Singapore are the rare examples of countries that are doing well economically without allowing political freedom. In the majority of cases, however, such as in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, it has only been after the establishment of democracy, or alongside it, that countries have flourished economically. Even low-income democracies and transitioning democracies perform better than their authoritarian counterparts, according to “The Democracy Advantage,” by Mort Halperin, Joseph Siegel, and Michael Weinstein. Their research concludes that when it comes to most measures of development – infant mortality, life expectancy, literacy, agricultural productivity, etc., democracies of all income levels have performed 20-40% better than autocracies over the past 40 years. China (which is experiencing both significant challenges to the Party’s monopoly on power and a disconcerting crackdown under President Xi) and Singapore are not the right models to look to – rather it is the vast majority of countries that have pursued both democracy and economic development and have succeeded.

THE “FOCUSING ON SECTORAL ISSUES IS ENOUGH” ARGUMENT

Point: The best way to advance human rights is by empowering women by improving health, education, and employment opportunities. Once they have these opportunities, everything else will fall into place.

Counterpoint: Clearly, these are important issues and the development community should continue to work to strengthen these areas. However, there is a critical gap if political empowerment is left out. While having schools, clinics, and jobs is key for economic development, the ability to hold one’s government officials accountable for maintaining such development and continuing to devote resources to them is key to increasing the prospects that any of those advances will last. For a country to become self-sufficient economically, it must also be politically democratic, so that citizens are able to speak freely about their needs, organize themselves to advocate for those needs, and demand accountable, transparent and responsive government.

THE “DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS LEAD TO CHAOS” ARGUMENT

Point: The attempted democratic transitions in the Arab World have only led to chaos and violence, strengthening ISIS and other terrorist groups. Some countries are simply not ready – and may never be ready — for democracy and need authoritarian leaders to maintain stability.

Counterpoint: The chaos and violence are not due to democracy promotion efforts but rather to the legacy of decades of dictatorship, oppression, and lack of opportunity. Without democratic traditions to fall back on, it is more challenging and takes more time for certain nations to establish themselves as stable democracies. Rather than shying away from supporting these efforts, we should be more engaged, providing much-needed training and examples from not only the United States, but preferably from countries that have been through democratic transitions far more recently like Poland or the Czech Republic and, one hopes, Tunisia.

There are always going to be skeptics when it comes to promoting democracy and fundamental human rights around the world. However, in addition to it being morally right to support those who are fighting for their freedom, this stance is also in the United States’ best interest – both economically and with regard to our national security. Favorable results will take long term commitment, effort, and persistence. While we won’t get it right 100% of the time, we must always pursue this path.

HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND RULE OF LAW IN CHINA: MAKING THE CASE

BY THE DEMOCRACY & HUMAN RIGHTS WORKING GROUP

While experiencing rapid economic growth and episodic improvements in the rule of law over the years, Chinese citizens today face one of the world’s most oppressive regimes, with a major deterioration in human rights and civil liberties.

Activists and lawyers are under increasing threat of detention, harassment, and, if imprisoned, torture and denial of medical treatment.

During a two-week period last year, over 200 lawyers and their associates were detained. Authorities are imposing greater restrictions on the Internet; a national security law from July 2015 grants the government unprecedented authority over Internet usage; journalists are required to pass political ideology exams, citizens are denied the ability to vote in elections, and Tibetans, Uighurs and religious believers are often targeted for persecution.

Yet U.S. policy for decades has relegated human rights and democracy concerns far down the list of priorities with Beijing owing to China’s size and economic weight. This paper identifies ways to elevate the importance of democracy, human rights and rule of law in China going forward.

I. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HOW TO PRESS CHINA ON HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND RULE OF LAW:

- Highlight specific abuses by the Chinese government – e.g., each U.S. Cabinet member could raise an individual political prisoner’s case with the Chinese government.

- Present a strong, consistent front by coordinating messaging by senior U.S. officials and by coordinating policy and messaging with allies. This should include publicly condemning violations of human rights and speeches on China that include explicit concerns about problems in the area of human rights and rule of law.

- Impose consequences on Chinese officials responsible for gross human rights abuses. One way to do this would be via pending Global Magnitsky legislation.

- Meet regularly at very senior levels with Chinese dissidents and activists – including Tibetans and Uighurs as well as religious believers – to demonstrate support for them.

- Fund technology and Internet circumvention applications and protect content generated by Chinese users to support freedom of information and communication within China.

- End the Human Rights Dialogue with China, which has proven to be not only ineffective but harmful by stove-piping human rights and democracy issues when instead they need to be incorporated into the broader bilateral agenda, including on the Bilateral Investment Treaty and Strategic & Economic Dialogue agendas.

- Provide breakdowns of the human rights situation by province in the annual Human Rights Report to highlight the worst and best areas. This will allow U.S. companies to invest responsibly, possibly spurring a race to the top as provinces compete to attract foreign investment by improving their human rights rating.

- Limit the use of Blair House and other symbolism – and even visits to the U.S. – to representatives from democratic countries, thereby exploiting the importance China attaches to prestige and status. High levels of emigration to and study in the U.S. demonstrate that the Chinese still hold the U.S. in high regard.

II. WHY WE SHOULD PRESS CHINA ON ISSUES OF HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND RULE OF LAW:

- From a purely moral argument, the U.S. should speak out on human rights abuses wherever they are committed, especially in a country as important and powerful a global player as China. It is simply the right thing to do.

- Left unchallenged by the U.S., Chinese authorities will see no incentive to change their behavior, making it likely that the current crackdown will get worse and emboldening China to continue trying to undermine norms beyond its borders.

- Chinese activists look to the outside world, especially the U.S., to speak out against abuses in the spirit of defending universal human rights.

- U.S. policy should reflect an investment in relations with the Chinese people over the long run, not only in the current, Communist Party-run government. With long memories, the Chinese people in the future should recall an America that stood in favor of their rights, even when they were abridged at home.

- Despots in other countries are less likely to respond to U.S. pressure on democracy and human rights issues if they see that China is getting a pass.

- It is in the U.S. interest for China to respect human rights, democracy, and rule of law.

- Given its complexity and mix of issues that unite and divide us, a China that better respects universal rights would put ties with the United States on a firmer foundation. The current weak rule of law and restrictions on civil liberties harm U.S. economic interests, for example through making it harder to build a mutually beneficial bilateral relationship.

III. ANTICIPATING COUNTER-ARGUMENTS:

Argument: “Too much to lose.” Pressuring China on human rights could jeopardize American financial interests, given China’s large stake in U.S. debt.

Response: Continued ownership of U.S. debt is in China’s financial interest, making it unlikely that Beijing would forfeit this solid investment and collect on U.S. debt in retaliation. Indeed, China’s investment in the U.S. is not contingent upon American silence; it is likely to hold U.S. bonds irrespective of Washington’s position on human rights.

Argument: “We cannot jeopardize other areas of cooperation.” U.S.-China partnership on other key issues – climate, nonproliferation, counterterrorism – would be damaged if we took a more aggressive approach on human rights.

Response: China will not back out of other negotiations or cooperation on other issues just because the U.S. pushes on human rights and democracy. Beijing pursues such cooperation out of national interest.

Argument: “Other countries are worse.” So why pick on China?

Response: China represents a fifth of the earth’s population and seeks a global leadership role. The state of universal human rights is thus of abiding importance, not only within China but beyond. Furthermore, the human rights situation under Xi has precipitously declined and shows no signs of improving.

Argument: We have a full plate of bilateral priorities; raising human rights issues would crowd out dialogue on cyber security, the maritime commons, etc.

Response: Human rights in China will not be the only bilateral issue with Beijing, or even always the top one. The key is to integrate concerns for human rights in China with all of the other issues the United States cares about.

HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND RULE OF LAW IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO: MAKING THE CASE

BY THE DEMOCRACY & HUMAN RIGHTS WORKING GROUP

When it comes to Africa, the George W. Bush administration launched its life-saving Malaria, Tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS initiatives last decade, and President Obama unveiled his “Power Africa” program in 2013. But beyond these important initiatives, the African continent is often overlooked by U.S. administrations focused elsewhere, despite its size, population (more than 1.1 billion people), vast natural resources, and impact on global stability and prosperity.

For that to change, the next administration must develop tailor-made approaches to a select number of countries, seeking to help them on the path to democratic development and a more prosperous society.

One of the most important countries on the continent is the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). With a population of 80 million, the Congo is one of Africa’s largest and most turbulent nations, having endured brutal colonial occupation, dictatorships, local warlords, conflict, poverty and disease. After gaining independence in 1960, the Congo endured thirty-two years of rule under Mobutu Sese Seko, who seized power in a 1965 coup. His reign ended after a rebellion in 1997 led by Laurent Kabila, with strong support from Rwanda and Uganda. Kabila was assassinated in January 2001, and his son, Joseph, became head of state. Joseph Kabila finalized a peace deal in late 2002 with the differing warring factions and also called for the withdrawal of Rwandan, Ugandan and other African troops from the Congo. Up to 5 million died as a result of the conflict, making it one of the deadliest since World War II. Tensions in the east have continued, heightening political instability in the country as a whole. Kabila was elected president in 2006, and in 2011 was reelected in a process that was widely criticized as illegitimate. Under the Congolese constitution, he is limited to the two terms he has already served and should be making way for his successor following new elections which are supposed to occur before the end of this year.

The Congo is a huge country, equivalent in geographic size to one-third of the United States, located in the heart of Africa. It is a complex country, with more than 200 different ethnic groups, and is the largest French-speaking country in the world. It is also rich in natural resources – and control over these resources has often been the source of terrible violence. Indeed, corruption and fighting in the east have badly stunted the country’s growth. The failure to respect human rights has been one of the Congo’s biggest problems, as evidenced by the staggering number of casualties. Thus, the U.S. needs an approach to the Congo that emphasizes the importance of democracy, rule of law, and human rights. Recommendations for working with the Congo on these issues include:

- Reinforcing the importance of holding free and fair presidential elections by the end of this year. This involves ensuring proper and transparent voter registration and an inclusive political process. Should it prove technically impossible to hold an election within this timeframe, President Kabila should still vacate his seat and allow the President of the Senate to take power as provided for in the constitution. The President of the Senate would have limited powers, with his chief mandate being the holding of elections within 90-120 days.

- Pressing the incumbent president, Joseph Kabila, to abide by the two-term limit set by the constitution and to step down when his current term ends later this year. A peaceful political transition through elections is essential.

- Emphasizing the importance of democratic institutions and providing robust international support for programs to strengthen political parties, civil society, and electoral institutions. Congolese are very committed to participating in elections and to institution-building, but often these aspirations are blocked by political figures and outside actors.

- Stressing the importance of democratic development at the local level. This is vital to bringing better governance to the people of the Congo, which in turn is essential to reversing the cycle of decline that has afflicted the country for years.

- Empowering not only the U.S. Ambassador in Kinshasa but also the Special Envoy for the Great Lakes and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, who, in that position, can play a critical role in promoting stability and reconciliation in the troubled east, as well as the whole region, by making clear the steps that need to take place for the DRC to emerge from its cycle of decline.

- Underscoring that the United States attaches great importance to the democratic future of the country, unlike other major outside actors that are more interested in doing business and exploiting the country’s natural resources and labor.

- Encouraging the UN to hold President Kabila accountable for the internal political instability, violence and corruption within the country.

- Condemning in no uncertain terms arrests and harassment of activists, journalists, and opposition figures, if they occur.

- Supporting development of entrepreneurship and economic development. If harnessed responsibly, the Congo’s natural resources could turn the country into a prosperous member of the continent.

- Enforcing and expanding, if necessary, existing U.S. Executive Order 13413 that calls for sanctions on those who continue to contribute to the conflict in the DRC.

- Using future meetings of the African Leaders’ Summit as opportunities to showcase those leaders who have held successful democratic transitions and can serve as examples to others.

HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND RULE OF LAW IN EGYPT: MAKING THE CASE

BY THE DEMOCRACY & HUMAN RIGHTS WORKING GROUP

The relationship between the United States and Egypt has always been a complex one. In the first place, Egypt has the largest population in the Middle East and carries significant weight in the region, in particular regarding the Israeli/Palestinian conflict.

Second, as part of Egypt’s 1979 peace treaty with Israel, it has received more than $70 billion dollars in U.S. government assistance, primarily to its military. Third, the human rights situation, which was bad under the 30-year autocratic regime of Hosni Mubarak, has deteriorated significantly under President Abdel Fatah al-Sissi, who was elected in June 2014 with 95 percent of the vote following a coup in July 2013 that removed the duly elected leader Mohamed Morsi; Sissi was elected without any significant competition or independent verification of the results. Without question, the U.S. and Egypt need to cooperate in the fight against terrorism, considering the violence taking place throughout the region, including Egypt’s own Sinai Peninsula, and the threat posed by extremist groups. However, the repressive tactics that Sissi has employed since his election are serving to increase radicalism and fuel terrorism, not deal with it effectively. By imprisoning critics, bloggers, and activists–as well as declaring the country’s largest opposition movement, the Muslim Brotherhood, to be a terrorist organization–Sissi fails to distinguish between true threats to Egypt and people who disagree with him, and risks radicalizing what might otherwise be peaceful opposition.

According to The Washington Post, Sissi is responsible for “the most severe political repression in Egypt in more than a half-century.” There are at least 40,000 political prisoners in Egyptian jails along with rampant torture of detainees, a crackdown on media freedom and civil society, and the excessive use of force against civilians in the name of counter terrorism in the Sinai. Despite Sissi’s efforts to maintain “stability,” an insurgency by Egyptian militants who have affiliated themselves with the Islamic State has increased in intensity and spread from the Sinai into the Nile Valley during his tenure. Moreover, the case involving four American organizations – Freedom House, IRI, NDI, and ICFJ – as well as Germany’s Konrad Adenauer Foundation, in which 43 employees were convicted in 2013, was recognized by the U.S. government, the EU, and others as politically motivated. It remains unresolved and has sparked a wave of repression against democracy and human rights organizations in the region. The person behind these events, Fayza Abul Naga, has been elevated to Sissi’s national security advisor. Dozens of Americans and Egyptian employees of American organizations remain unable to travel as a result, separated from their families, and barred from many employment possibilities due to their convictions in the case. The United States government is, in the minds of some, complicit in these human rights violations because it provides the Egyptian military with $1.3 billion in assistance annually, including weapons that may well be used in human rights abuses against civilians. Except for a brief period during which some weapons deliveries were delayed after the 2013 coup, that assistance program has remained largely unchanged over the years, notwithstanding the revolution of 2011 and all that has happened since. Continuing down the same policy and assistance paths risks hurting U.S. national interests.

Accordingly, there is a serious need to reevaluate the U.S. relationship with Egypt so that our aid goes to legitimate counter-terrorism operations and does not finance repressive acts by the authorities. The Obama administration has taken an important step down this path by ending the cash-flow financing arrangement that previously allowed Egypt to purchase billions of dollars in military equipment on credit. This arrangement was predicated on the expectation that Congress would continue appropriating the same amount of assistance to Egypt each year because the U.S. government would be liable for millions in penalties should the assistance ever be reduced or cancelled. But more can, and needs, to be done.

Recommendations for reevaluating the U.S./Egypt relationship and pressing Egypt on human rights, democracy, and rule of law issues include:

- Make clear publicly and privately that human rights abuses lead to increased radicalization and terrorism, and that Sissi’s policies are producing the very scenario he claims to be addressing.

- Stress that good governance and human rights go together, and help bolster security and stability.

- Rebalance current U.S. assistance, which includes $150 million in economic aid and $1.3 billion in security assistance, based on an updated assessment of Egypt’s current economic and security needs. Consider making a much larger investment in education for Egyptian youth, who are now marginalized and in danger of becoming radicalized.

- Require a holistic and viable political, economic, and security strategy on counter terrorism from Egypt before supporting the allocation of funds, and reattach human rights conditions to U.S. assistance.

- Restore assistance to beleaguered civil society organizations – both registered and unregistered — to be delivered through non-governmental organizations rather than directly from the U.S. government.

- Refuse to meet with Fayza Abul Naga, who as minister of planning and international cooperation led the criminal charges against U.S. and other democracy and human rights NGOs, and was appointed national security advisor by President Sissi in late 2014.

- Demand that Egypt pardon all those convicted in the NGO case.

- Take up specific political prisoner cases and raise them at the highest levels of the Egyptian government from the highest levels of the US Government.

Along with other Western democracies, support the Egyptian human rights community through direct financial and programmatic assistance. - Couple direct economic aid with incentives that would encourage Egypt to strengthen market institutions, rule of law, and property rights, to expand economic opportunity for all Egyptians and contribute to sustainable economic growth. Such incentives could include greater integration into global markets and Egypt’s ability to attract increased foreign direct investment.

- Make sure that senior U.S. officials – Cabinet-level as well as the President – meet with Egyptian activists and civil society representatives, whether officially registered with the Egyptian government or not, either during visits to Cairo or in DC.

- Ensure in every interaction with Egyptian officials, including the Strategic Dialogue and mil-mil talks, that human rights concerns feature prominently on the agenda and discussion.

HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND RULE OF LAW IN ETHIOPIA: MAKING THE CASE

BY THE DEMOCRACY & HUMAN RIGHTS WORKING GROUP

Within the development assistance community, Ethiopia often is cited as a “success” story. “Over the last decade,” according to USAID’s website, “Ethiopia has made tremendous development gains in education, health and food security.” And yet Ethiopia over that same rough time period has experienced a massive decline when it comes to democracy, human rights and rule of law. Even when it comes to food security, Ethiopia is experiencing yet another crisis this year, so its progress in that area is debatable.

Ever since seizing power in 1991, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) has maintained a tight grip on power, especially following parliamentary elections in 2005 that sparked serious violence against opposition forces, with roughly 200 killed. During the past decade, the EPRDF has systematically harassed and intimidated opposition figures, restricted space for civil society, and censored and imprisoned journalists and bloggers; it is one of the worst offenders in press freedom. In the most recent parliamentary election in 2015, not a single opposition deputy was able to secure victory, as EPRDF and affiliated parties secured all 547 seats.

As Freedom House reported in its most recent annual assessment, the government in Addis Ababa “used the war on terrorism to justify a deadly crackdown on protests against forced displacement in the Oromia region…as well as ongoing repression of political opponents, journalists, bloggers, and activists.” The first peaceful transition in leadership in decades at the top came in August 2012, when longtime Prime Minister Meles Zenawi died in office and was replaced by his Deputy Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, though this transition was decided by a small clique, not a democratic process.

With a population approaching 100 million, Ethiopia is located in the strategic Horn of Africa, surrounded by states with varying degrees of challenges, from Somalia and Eritrea (with which it has sporadically fought for years) in the east to Sudan and South Sudan in the west and north. And yet the EPRDF’s stranglehold on all levels of political and economic life is pushing the country’s major ethnic and religious groups – and there are more than 80 different ethnic groups — into adopting means other than constitutionally prescribed channels to air their grievances, some of which are decades old. Between 30 and 40 percent of Ethiopia’s population lives below the poverty level, with per capita income among the lowest in the world. Even though the economy remains largely agriculturally-based, hunger and even famine have been recurring issues challenging the government and Ethiopian people, and food aid has at time been used to reward government supporters and punish opponents. Ethiopia is at a crossroads, with virtually every democracy/human rights indicator pointing in the wrong direction. There is a need for a full review of U.S. policy, which over the years has seen security concerns and food aid trump U.S. interests in seeing Ethiopia move on a more democratic, rule-of-law based path. Thus, recommendations for the next U.S. administration working with Ethiopia on democracy and human rights include:

- Including development of democratic institutions, rule of law, good governance, and gender equality at the top of the list of U.S. priorities for Ethiopia (and Africa as a whole, for that matter), along with our security and economic interests.

- Resisting an either-or choice between advancing our security interests with Ethiopia and our democracy/human rights interests. We need to emphasize that these interests are compatible, and, in fact, a more democratic Ethiopia would likely be a more reliable partner on security challenges and more secure in its own right, as well as have better prospects for economic growth and development.

- Pushing for proper funding levels for such assistance and finding creative ways to support indigenous organizations that face severe restrictions on foreign funding, including offshore programs and assistance for civil society groups. This should also be based on “lessons learned” from past assistance programming and include a small business component.

- Conditioning other assistance, including African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) trade preferences on Ethiopia’s meeting certain democratic criteria; the Millennium Challenge Corporation already has such conditionality and Ethiopia consequently does not qualify for MCC assistance.

- Pressing authorities for more openness and access for the Internet and telecommunications and an end to its campaign against journalists and bloggers.

- Ramping up digital outreach to Ethiopian society and working to break the information monopoly maintained by the EPRDF.

- Speaking out against the politically monopolistic practices of the EPRDF, such as full control of the parliament, and against the broader crackdown on civil society. Revoking the repressive Charities and Civil Society Proclamation should be a focus.

- Sanctioning government officials involved in serious human rights abuses. Passing the Global Magnitsky Act would be one way to achieve this.

- Coordinating efforts to support democratic development in Ethiopia with allies both on the African continent and in Europe, as well as with international organizations, and helping reduce the isolation of Ethiopian civil society from the rest of the region.

The need for the last bullet above is reinforced by the fact that Ethiopia hosts the African Union. The diversity and scale of Africa as a whole make it difficult to generalize about the continent, though it is clear that democracy has been under attack as a number of entrenched African leaders refuse to give up power and Islamist extremists threaten life and wreak instability. Successful elections and peaceful transfers of power in places like Nigeria and Cote d’Ivoire have been overshadowed by serious problems in Burundi, Uganda, Niger, and the DRC. And even where smooth transfers of power have occurred, as in Nigeria, for example, huge challenges are posed by the terrorist group Boko Haram. Indeed, for the continent as a whole, U.S. policy needs to elevate the importance of democracy, human rights, and rule of law, including through an increase in funding for such interests. It should emphasize the role of civil society and engage in broader outreach to young activists through a White House-led forum. It should consider establishing a Democracy Fund for Africa and press to have parallel vote counts and election observation missions standard practice. The use of information technology such as digital messaging also needs to receive more support.

HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND RULE OF LAW IN IRAN: MAKING THE CASE

Hassan Rouhani in June 2013 would lead to an opening of the political and civil space in Iran that has been closed for so long. Unfortunately, under President Rouhani, who is either unwilling or unable to challenge the hardliners in the regime, not only is Iran still the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism, but its human rights record has also dramatically worsened. Critics of the regime are routinely arrested, torture is widespread, minorities and women are treated like second class citizens, journalists are imprisoned, and due process is essentially nonexistent for individuals accused of “national security” crimes.

A 2015 law denies defendants the right to choose an attorney if accused of breaking national security laws. Under Rouhani, executions have also increased, to the point that the United Nations has expressed “alarm” at the “exponential rate” of increase in the number of death penalty cases. According to Amnesty International, in 2015 Iran was one of three countries responsible for 89% of that year’s recorded executions (excluding China). At least 977 were executed in 2015, “more individuals per capita than any other country in the world,” according to Ahmed Shaheed, UN special rapporteur for Iran. Incredibly, since being appointed five years ago, Dr. Shaheed has not been permitted to enter Iran or to meet with Iranian refugees in democratic countries such as Turkey and Australia.

For several years, the focus of the United States government and democratic allies was on reaching a nuclear agreement with Iran. Now that an agreement has been reached, it is important that the U.S. and Europe turn their attention to the worsening human rights situation there. The lack of attention on human rights has given the Iranian regime the sense that it can get away with its internal crackdown. We need to work with other democracies to address Iran’s appalling human rights record.

Recommendations for how to press Iran on human rights, democracy and rule of law include:

- Shine a brighter spotlight on the deteriorating human rights situation with a concerted campaign to publicize the plight of women, minorities and political prisoners.

- Demand the immediate release of all political prisoners and detained American citizens.

- Push for access for the UN special rapporteur for Iran and for his mandate to be renewed and extended.

- Press Iran to agree to allow credible international monitoring presidential and municipal elections in 2017.

- Make use of the international network created during the nuclear negotiations and work to pass a UN resolution on Iran that outlines the human rights concerns of the international community and sets clear benchmarks for progress. The European Union’s participation is critical.

- Support programs to train Iranian civic activists, judges, lawyers and others about their rights and advocacy techniques. Again, EU involvement in supporting Iranian civil society is very important as it makes it harder for the regime to justify its crackdown by claiming CIA or British intelligence plots are behind the civil society efforts.

For several years, the focus of the United States government and democratic allies was on reaching a nuclear agreement with Iran. Now that an agreement has been reached, it is important that the U.S. and Europe turn their attention to the worsening human rights situation there.

- Increase opportunities for ordinary Iranians to study in the U.S. and other western countries and participate in non-political cultural, social and academic work.

- Increase US broadcasting into Iran, but with a focus on reaching the non-intellectual class that is not fully aware of the regime’s heinous actions against its citizens or its foreign policy actions and would benefit from civic education. The key is to provide solid, fact-based journalism, giving Iranians the news and information they want and need and which their government denies them.

- Ramp up targeted visa bans and targeted sanctions against the worst human rights offenders, primarily in the judiciary and the Guardian Council.

- Consider a Commission of Inquiry on Iran at the UN Human Rights Council to address longstanding human rights abuses.

HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND RULE OF LAW IN MEXICO: MAKING THE CASE

By The Democracy & Human Rights Working Group

Mexico is an important ally of the United States, not only because of its geographic proximity but also because of the economic and trade relationship that exists between our two countries. A strong, democratic, prosperous Mexico is in the interest of Mexicans, first and foremost, but also important for the United States and the entire region. Our countries also share an interest in combatting drug trafficking, reducing violence, eliminating impunity, and ensuring that criminals are brought to justice.

Mexico has adopted important reforms to its criminal justice system in recent years. In 2008, Mexico passed a series of constitutional and legislative reforms designed to make its justice system more effective, efficient, and transparent. In follow-up to these reforms, in March 2014, the Mexican Congress approved the National Code of Criminal Procedure. These reforms transformed the legal system to an adversarial judicial model and created important legal protections such as access to and confidential communication with a lawyer from the moment of detention; the right to the presumption of innocence; making the use of torture illegal; and informing detainees of their rights and the acts for which they are accused. In June 2014, the Code of Military Justice was amended to allow cases of civilian victims of human rights violations to be tried in a civil rather than military court. The Mexican government has also been active in promoting human rights in the United Nations and in other international and regional fora.

Unfortunately, the existence of these laws has not translated into effective implementation of these protections. According to a report issued by U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture Juan E. Mendez in December 2014, “torture is generalized in Mexico” and frequently used in various parts of the country by “municipal, state and federal police, state and federal ministerial police and the armed forces.” Disappearances are widespread in many parts of the country, with government officials involved in numerous cases. Mexico also continues to experience high levels of violence, including several incidents of extrajudicial killings involving federal security forces in recent years. The Mexican government denies these findings, though the abuse takes place at all levels: federal, state and local. Only five federal convictions for torture were reported by the government between 2005 and 2013, demonstrating widespread impunity for human rights violations.

Mexico passed a series of constitutional and legislative reforms designed to make its justice system more effective, efficient, and transparent.

To truly flourish, Mexico needs a strong justice system based on the rule of law and accountability, as well as an end to impunity. The United States, as one of Mexico’s closest partners, should continue to engage Mexico in this effort. Recommendations for working with Mexico on human rights and rule of law issues include:

- Continuing current US government programs to professionalize the police and limit, control, and gradually reduce the military role in policing; to create or strengthen internal affairs units that are capable of self-investigation; to strengthen judicial reform efforts; and to provide support for rapid response safety measures to human rights defenders and journalists.

- Continuing bilateral human rights dialogues to engage with the Mexican government on the need for increased human rights protections.

- Providing support, both programmatic and in terms of public expression, to civil society groups, especially at the state level, that are struggling to bring attention to cases of abuse, pressing for accountability for human rights abuses, and calling for an end to impunity.

- Working with other regional governments, such as Colombia or Chile, as well as the Organization of American States and the United Nations, to develop a strategy for engaging with Mexico on rule of law issues.

- Engaging with Article 19, Reporters without Borders, Amnesty International, Freedom House and other international human rights and freedom of expression organizations to press for reform and provide assistance to human rights defenders and journalists in Mexico.

- Identifying creative ways for dialogue on judicial reform issues, such as through organizing an investment climate meeting that would include discussion of corruption, rule of law, and the informal sector.

- Considering the merits of requesting a U.N. or regional commission of inquiry to work with Mexican prosecutors to investigate cases of grave human rights violations, including the case of 22 civilians who were killed by Mexican soldiers in the state of Mexico in June 2014 and supporting the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’ (IACHR) follow up mechanism to the work and recommendations of the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts named by the IACHR to provide technical assistance to the government on the case of 43 students who disappeared while in the custody of local police in the state of Guerrero in September 2014.

HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND RULE OF LAW IN NIGERIA: MAKING THE CASE

BY THE DEMOCRACY & HUMAN RIGHTS WORKING GROUP

Nigeria is a country of contrasts – a dynamic, fast growing, religiously diverse, and fairly democratic country that also has a history of military coups, is besieged by poverty and corruption, “cursed” with large reserves of oil, and is home to one of the world’s most deadly terrorist groups.

It is Africa’s most populous country (more than 180 million people, making it the 7th largest in the world); and it boasts the largest economy on the continent (besting Egypt and South Africa). While the economy has become somewhat more diverse, Nigeria depends heavily on oil production. With oil prices plunging globally, in 2015 its economy grew at about half the rate as during the previous decade, affecting both the energy industry and the government, which receives about 80 percent of its revenue from oil exports. Fighting continues in northeastern Nigeria between government security forces and the terrorist group Boko Haram, which employs guerilla-style attacks and suicide bombings against both civilian and government targets; it has killed tens of thousands, displaced over two million, and has become a full blown regional conflict spilling over into Cameroon, Chad and Niger. According to Freedom House, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International as well as numerous domestic groups, Nigeria’s security forces are also guilty of committing human right abuses, including thousands of extrajudicial killings, illegal detentions, torture, and arbitrary mass arrests. Further, corruption is rampant both within the Nigerian government and in particular in the state-run oil company, resulting in the loss of potentially billions of dollars.

On the positive side, 2015 witnessed a peaceful transfer of presidential power from incumbent Goodluck Jonathan to Muhammadu Buhari after the opposition won national elections at both the presidential and legislative level for the first time in competitive and well-run elections. President Buhari, a former general and military head of state, has taken some steps toward fighting corruption, defeating Boko Haram, and improving the living standards of Nigerians. He replaced the head of the lead anti-corruption agency, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, and empowered it to seek out and investigate officials at all levels, despite challenges from Nigeria’s bureaucratic judicial system. He also installed new leadership at the Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation, the state oil company, which has instituted new transparency standards. Oil is at the heart of many of Nigeria’s problems and with low oil prices, a shrinking economy, and higher inflation, the oil-producing Delta region is showing signs of increased violence and conflict. Before Boko Haram, the Niger Delta region was the epicenter of oil-related violence until the government in 2009 offered amnesty to certain militant groups. A resurgence of militant groups in this area would strain an already overstretched military force and likely result in more human rights violations. While President Buhari implemented military reforms, coordinated intelligence sharing with several African countries, and managed to recapture a significant amount of territory from Boko Haram – though they are having trouble holding on to it — a two front military effort in the north and southeast would set Nigeria on a very dangerous path of increased violence and bloodshed. Given its sheer size, oil production, and contributions to international peacekeeping, Nigeria is arguably one of the most important African countries, particularly to the United States. While it has numerous internal challenges, its population and economy make it an important partner on counter terrorism, as well as a significant player geopolitically and in the world economy. It is a key regional leader with enormous potential, but it needs to improve economic conditions to bring stability and security to all its people. Recommendations for working with Nigeria on democracy and human rights include:

- Approaching President Buhari about enhancing military-to-military relations with a focus on professional training, strengthening human rights standards, establishing accountability, and identifying ways to fight Boko Haram while minimizing the displacement and abuse of citizens. The police forces should receive similar training and establish appropriate rules of engagement, while Civilian Joint Task Forces – civilian groups formed to fight Boko Haram – should be monitored and efforts made to provide them with gainful employment.

- Imposing consequences on Nigerian officials responsible for gross human rights abuses. One way to do this would be via pending Global Magnitsky legislation. At the very least, the U.S. should implement the visa sanctions that it stated it would impose against human rights violators during the 2015 elections.

- Pressing for the immediate closure of detention centers that do not meet international human rights standards; release of all detainees who have not been charged with a crime; access for charged detainees to a lawyer and basic services such as through visits by the International Committee of the Red Cross or other independent monitoring organizations; as well as a fair trial for all remaining detainees.

- Providing material and technical support to domestic civil society groups that are working to highlight human rights abuses. In addition to providing consistent support throughout the year, the U.S. should organize a White House-led forum to emphasize the role of civil society and engage in broader outreach to young activists, not only in Nigeria but throughout Africa.

- Continuing to support political parties, civil society groups and electoral stakeholders in their efforts to build a solid democratic foundation strong enough to withhold any challenges to the progress made in the past two decades.

- Supporting President Buhari’s efforts to tackle grand corruption within the federal government and encouraging greater transparency and reforms at the state oil company.

Encouraging the next U.S. president to visit Nigeria to highlight and demonstrate support for the recent democratic transition. - Using future meetings of the African Leaders’ Summit as opportunities to showcase leaders such as President Buhari who have held successful democratic transitions and can serve as examples to others on the continent when it comes to respecting human rights, rule of law, and democratic norms and institutions.

- Stressing the importance of democratic and economic development at the state and local level. Nigeria is made up of 36 socially and economically diverse states.In certain states, like Kaduna and Lagos, governors have taken the initiative to institute policy reforms to increase revenue, improve governance, and reduce corruption. Such efforts should be supported.

- Revitalizing the U.S.-Nigeria Business Council to inspire private sector investment and engagement in Nigeria’s economy and to strengthen the non-oil sector.

- Considering establishing a U.S.-Nigeria Human Rights Dialogue to highlight and identify areas where progress can be made to support human rights in Nigeria, as long as other U.S. government officials continue to raise such issues along with the assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights and labor.

- Strengthening AGOA opportunities, continuing support for Power Africa, and working with Nigeria on possible membership in the Open Government Partnership as a means of improving transparency, accountability, and democratic governance.

HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND RULE OF LAW IN RUSSIA: MAKING THE CASE

BY THE DEMOCRACY & HUMAN RIGHTS WORKING GROUP

Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia has experienced the worst crackdown on human rights in decades while becoming one of the biggest kleptocratic regimes in the world. Anti-Western and anti-American rhetoric, directed by the Kremlin to justify its authoritarian methods, paints the United States, NATO, and the EU as threats to Russia. Opposition figures as well as journalists and commentators critical of the government are demonized as enemies of the state, creating an environment in which an opposition leader like Boris Nemtsov can be gunned down yards from the Kremlin and others are harassed and intimidated, and in a number of cases forced to flee the country.

Domestically, the Kremlin has waged a concerted campaign to limit NGOs from working on sensitive issues like human rights and/or receiving foreign funding. Amendments to the NGO law passed in 2012 required NGOs receiving outside funding to register as “foreign agents”, branding them with language reminiscent of Soviet times.

In May 2015, Putin signed a law allowing foreign firms or NGOs to be designated as “undesirable”, requiring them to close their offices and any operations in Russia or else risk having their accounts frozen and their staff and any other partners subject to administrative or even criminal penalties. The so-called Yarovaya Law (named after its author in the lower house of parliament, or State Duma), enacted in July 2016 and ostensibly designed to combat terrorism, threatens civil liberties by significantly expanding the definition of terrorism, making it a crime to not report a very long list of other crimes, and requiring IT companies to provide a back door to the government for all encrypted networks and store telecom data for up to six months, which the telecommunications industry estimates could cost billions of dollars. Additional legislation has been passed restricting the work of missionary groups and organizations.

Parts of the country, especially the North Caucasus, suffer from brutal treatment by authorities, with one of the worst examples being the administration of Ramzan Kadyrov in Chechnya. Immigrants, LGBT, religious and ethnic minorities are discriminated against and harassed. Dozens of NGO workers and activists have been arrested and charged with political crimes, including terrorism, separatism, and incitement to racial hatred, especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Although some U.S. donors and many European ones continue to find ways of operating in Russia, the “undesirables” law has led a number of major private American donors to pull out of Russia, leaving a big gap in funding for local civil society organizations.

Elections are scheduled in the fall of 2016 for the State Duma, and United Russia, the “party of power,” is once again expected to win the majority of seats; the remaining seats will likely be won by parties that are not truly in opposition to the government. In the lead-up to the vote, the government continues to stifle opposition politicians and parties, even imprisoning the brother of Aleksey Navalny, an anti-corruption campaigner and politician, in an attempt to rein him in. At the same time, in an indication of Kremlin nervousness caused by major protests the last time Duma elections took place in December 2011, Putin in April announced the creation of a 400,000-man National Guard under his close ally, Viktor Zolotov, to deal with domestic disturbances and protests. Its creation also may have been a way to consolidate power in hands trusted by Putin.

As Russia’s domestic repression has deepened, its authoritarianism and kleptocracy have gone global, constituting a serious threat to U.S. interests.

Since Putin came to power, he and Russia have benefitted from the high price of oil that has led to a significant improvement in the standard of living, though Russia’s economic performance started stalling before the drop in the price of oil. Last year, the economy shrunk by 3.7 percent due to falling oil prices, Ukraine-related sanctions, and overall economic mismanagement by the government, including a failure to diversify away from natural resource dependency. Russian GDP is predicted to drop another 1.5 percent this year. Putin’s approval ratings have fallen slightly, and Russian citizens are feeling the pain of an insufficient social safety net, with sporadic protests breaking out in various parts of the country. The Kremlin, meanwhile, continues to award contracts in the billions of dollars to Putin’s cronies and pet projects, and its kleptocrats launder and invest their stolen funds in the West – at the same time that they lambaste the West.

As Russia’s domestic repression has deepened, its authoritarianism and kleptocracy have gone global, constituting a serious threat to U.S. interests. The Putin regime projects its malign influence internationally through state-backed disinformation and propaganda via global media outlets, political manipulation throughout Europe, the export of corruption, and old-fashioned hard power, as in Ukraine and Syria. By propping up Syria’s dictator, Bashar al-Assad, Russia has contributed to the ongoing and violent civil war there. It tries to stir up separatist movements in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, not to mention its illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014 and continued aggression in Ukraine’s Donbas region. It has come to view efforts by its neighbors to deepen ties with the EU almost as much of a threat as NATO enlargement. It has also supported parties in Europe on both the extreme right and left flanks. At the same time, Russia is not abiding by its commitments as a signatory of the OSCE, Council of Europe, and Universal Declaration of Human Rights; on the contrary, it is attempting to place candidates unfriendly to human rights in various UN and other seats, including the seat of the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media. Russia’s actions embolden and serve as a model for other authoritarian regimes, such as China, Iran and Venezuela.

Although there has been limited cooperation between the U.S. and Russia on certain issues such as arms control, the Iran nuclear deal, and removal of chemical weapons and a ceasefire in Syria (that later broke down), U.S. relations with Russia for the most part have been badly strained, especially since Putin returned to the presidency in 2012. Putin’s ostensible internal popularity notwithstanding, the Russian people suffer from a government that is not accountable, trustworthy or representative, and the United States would have a better partner in an economically prosperous Russia that is also more democratic, albeit developed in its own way.

The challenge is not whether to engage or isolate Russia. Instead, it is the nature of the democracies’ engagement that must be rethought. Established democracies must pursue a more nimble and principled approach that takes into account the new environment in which Russia and other such authoritarian regimes are seeking to undermine democratic institutions and values. Accordingly, recommendations for the next U.S. administration working with Russia on democracy and human rights can be broken down into three broad categories:

DEFENDING DEMOCRATIC VALUES

- Articulating an overarching strategy on Russia that would include democracy and human rights issues and working with civil society as key components.

- Returning to a policy of “linkage” by making clear that the way Russian authorities treat their own people will affect broader U.S./Russia relations and that threats to Russian civil society will prevent both sides from having a productive, stable and mutually beneficial relationship.

- Meeting regularly at very senior levels with Russian dissidents and activists – both in Russia and in the United States – to demonstrate support for them.

- Expanding existing mechanisms and finding innovative ways to provide material and technical support to domestic civil society groups and grassroots initiatives that are working to support democracy, respect for human rights, and free and fair elections. This would include developing partnerships with European allies and international organizations to enhance such support.

- Exploring opportunities to support regional and local leaders who are working for democratic governance and rule of law.

COMBATTING RUSSIAN ABUSES AND KLEPTOCRACY

- Developing partnerships with journalists and NGOs to investigate and expose the widespread kleptocracy in Russia and pressing for greater enforcement of existing laws. If the Russian people are more aware of the extent to which their government has been corrupted, they are more likely to demand accountability and transparency.

- Implementing more aggressively the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law and Accountability Act and enacting into law the Global Magnitsky Act to sanction human rights abusers and kleptocrats. The U.S. should also urge other countries to adopt and implement similar legislation. As part of this effort, the U.S. should conduct an overall review of its sanctions list to target more of the elite complicit in such abuses.

- Concentrating U.S. government resources on tracing illicit financial flows to prevent Russian kleptocrats from investing and parking funds in the West. Enabling entities, like financial institutions and clearing houses that launder and invest funds in other markets, should also be targeted. This requires cleaning up our own systems, abiding by our own laws and ethical obligations, and blocking illicit Russian funds and their corrupting influence in asset-buying and laundering.

- Bolstering cooperation with other law enforcement agencies to go after Russian organized crime and corruption and aggressively pursuing cases like the FIFA investigation.

REINVIGORATING SOFT POWER

- Supporting a plurality of media organizations both in and outside Russia, individual citizen journalists, and the organizations that work in partnership with them to increase the availability of independent, professional news and information for Russians. A two-pronged approach where external media work together and in parallel with those within the country is needed to expose corruption, human rights violations, and infringements on political and civil liberties by the Russian government.

- Backing efforts to maintain internet freedom in Russia, which is in danger of being stifled as the Kremlin attempts to control it.

- Pressing Russia to live up to its UN, OSCE, Council of Europe and other international commitments on human rights. At the same time, resist calls to reconstitute the G-8 with Russia until it changes its ways internally and toward its neighbors.

- Conducting outreach to the Russian diaspora in the U.S. and other countries to mobilize them to support reform inside Russia and to press Western governments to pursue better policies on democracy and human rights concerns.

- Using American LNG exports to support a strong spot market in Europe to further depress the price of Russian natural gas exports to Europe and supporting the shift of the American transportation sector to electric and natural gas vehicles to lessen American use of petroleum, reducing global oil demand and, most notably, squeezing Russian petroleum profits.

Established democracies must pursue a more nimble and principled approach that takes into account the new environment in which Russia and other such authoritarian regimes are seeking to undermine democratic institutions and values.

SUPPORTING RUSSIA’S NEIGHBORS

- Reaffirming support for Russia’s neighbors, their sovereignty and territorial integrity, their Euro-Atlantic aspirations, and their development of a democratic, rule-of-law based foundation. This is important in its own right to help these countries succeed, but it has the added benefit of limiting Russia’s efforts to export its domestic policies and staunch the aspirations of other countries, as in Syria, where Russian adventurism, in a de facto alliance with Iran, is conspiring to maintain by force a repressive status quo.

- Maintaining sanctions — both U.S. and EU — on Russia for its illegal annexation of Crimea and invasion of and ongoing aggression in eastern Ukraine while preparing for the possibility for additional measures should the situation there deteriorate as a result of stepped-up Russian action.

HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND RULE OF LAW IN SAUDI ARABIA: MAKING THE CASE.

BY THE DEMOCRACY & HUMAN RIGHTS WORKING GROUP

The tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran present an opportunity to take another look at the U.S.-Saudi relationship, which has centered on business, arms deals (close to $25 billion in arms sales since the start of 2015), development of Saudi oil, regional stability, and counter-terrorism. At the same time, Saudi Arabia is one of the world’s most authoritarian regimes and worst human rights offenders.

Yet for decades, the U.S. has refused to criticize the Saudi Kingdom on human rights concerns. Successive American administrations have concluded that encouraging change is hopeless, instability in the Kingdom would be much worse, and Saudi Arabia’s role as the world’s swing oil producer is too important. No other country is treated with such kid gloves, notable given Saudi Arabia’s role in tamping down nascent democratic movements in other countries in the region (e.g., Bahrain) as well as its own.

New antiterrorism regulations that were passed in 2014 allow the Saudi government to criminalize nearly any form of peaceful opposition as terrorism. Minorities, especially Shia Muslims, are widely discriminated against, women’s rights are nearly nonexistent, and there are no elections of any kind at the national level, though women were allowed to vote for the first time in municipal elections on December 12, 2015.

Millions of migrant laborers, especially domestic workers, are highly vulnerable to forced labor and human trafficking, and are unable to escape situations of exploitation or violence. Nine million non-Saudi residents (out of a population of 28 million) have little to no access to justice; further, their embassies see little political space to defend their citizens’ rights. Saudi Arabia, without any real due process of law, executed more than 150 people in 2015, the highest recorded level since 1995; on January 2, 2016, it executed 47 people, including a prominent Shiite cleric, inflaming sectarian tensions across the region, especially with Iran. The United States – with rare exceptions – has been largely silent on these issues.